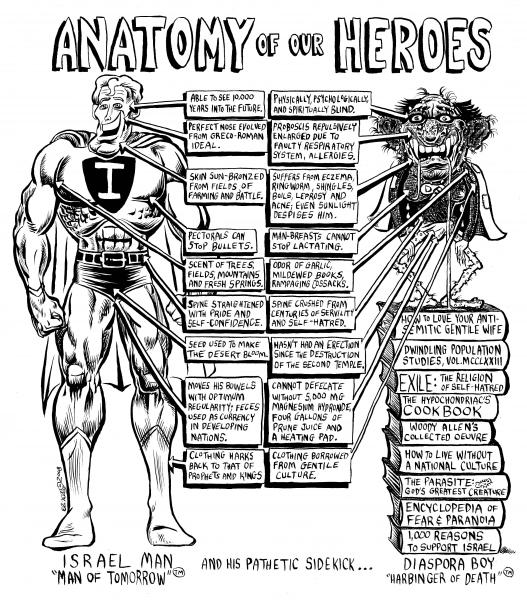

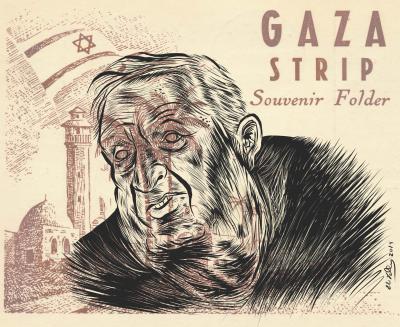

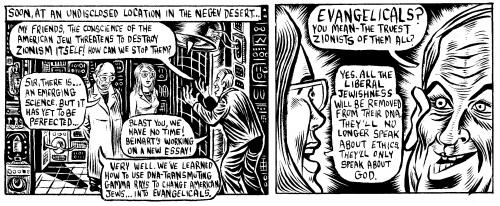

The most vivid and without a doubt, the most disliked (make that, hated) comic-artist critic of Jewish power plays, from Tel Aviv to Los Angeles, Eli Valley ranks high among the most Jewish comic artists anywhere in the world today. He has been publishing his comic art for less than a decade, and it appears most influentially in the (Jewish) Forward, the English-language heir to what was, a century ago, the most widely circulated Yiddish daily newspaper in the world. There, his satires on big shots Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, American billionaire Sheldon Adelson, Anti-Defamation League (ADL) boss (until his recent retirement) Abraham Foxman, and such, inspire outrage among politically conservative and other Israel First readers. His work also appears on line in +972 Magazine, the voice of the Israeli left and its allies, and doubtless meets a friendly reception there. But it’s not clear whether Eli enjoys appreciation or rage to any greater degree. He loves to stir the pot.

As a comic artist, he is also sui generis, even if he gives us good reasons to look for influences in the old comic book art and in some cases, fairly recent work. There is something about the Jewish, make that cryptic-Yiddish, identity of Mad Comics (1952-55) before the franchise became milder and aimed at younger readers. That something is an intensity, a vibrancy, that the Gentile artists also reflected toward Mad targets ranging from superhero comics to beer commercials to the McCarthy Hearings. It is an intensity rarely equaled. Mad Comics was the creation of young people, and perhaps that helps explain their psychic and artistic energy. Let’s hope that Eli Valley can hold on to that verve for decades to come. Paul Buhle

Paul Buhle. Your background offers some surprises—your father’s a rabbi and your parents are divorced. Did your secularish mom help give you a sense of contrast that found its way into your comics?

Eli Valley. There are a lot of streams that probably flowed together, but the divorce and the contrast between reverence and irreverence in my family played a part. But it’s also various experiences I had growing up. I went to Jewish day school through the eighth grade, and in some ways it was rigorous and critically minded, but in others—okay, Israel—it rubber-stamped a lot of stuff that maybe it’s better to question if you want to have your brain working at full capacity.

PB. And then after college you worked as a tour guide to Jewish Prague, home of Kafka and the triumphant return of Western consumerism, and so on. Was that another source of inspiration?

EV. Maybe it was, indirectly. I moved there after growing up in the Northeast, where we’re sort of saturated and satiated on everyday Jewish culture. We take it for granted, it’s ubiquitous, and the sense of power when you just look at the communal infrastructure alone is awe-inspiring. Coming from that culture and then moving to post-Communist Prague, I met all these young people who wouldn’t even think of taking Judaism for granted, because it had been sidelined, hidden, and persecuted over the previous decades. It was eye-opening to see people approach it as something new to cherish and value. I think I started looking at it that way only once I was outside of America. So I think my passion for Jewish culture and history came out of Prague.

I know I romanticize it, but that too is a Jewish tendency: idealization of earlier eras of supposedly pristine culture that we’re probably deluding ourselves about. But it was only when I came back to America, to New York, that I was reminded of the somewhat jaded attitudes towards the culture I grew up on. That can be expected in a place like America, where Jewish acceptance and accomplishment are unprecedented, but that didn’t make it any less jarring. It’s possible that sort of collision eventually found its way into my comics. And as a side note, living in Europe felt like an entry into Jewish history in ways I never felt in America or in Israel. European Jewish history is my heritage in ways that the Maccabees and Suez Canal fighters are entirely foreign to me—which is why I think a “Birthright diaspora” would be much more logical than “Birthright Israel.” Not to mention more generally Prague’s tradition of humor, savoring of free expression and the use of art and literature to subvert corrupt power structures, but that sounds arrogant so I’ll stick to my Ostjuden reverie.

PB. Your comics hit a nerve among American Jews and Israelis. Is there something about the current period we’re in? Why these kinds of comics now?

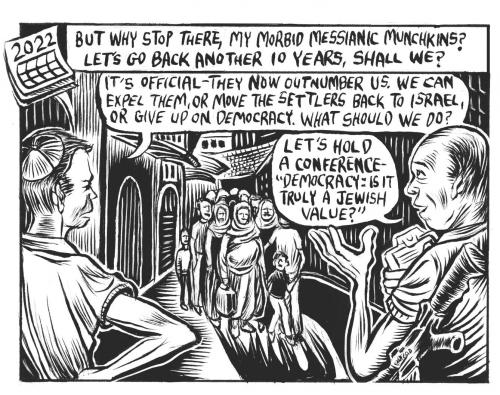

EV. Jewish satire has a long history, but I don’t think my particular style of comics and satire could exist outside a community that’s achieved an unprecedented degree of power. But also, I think we’re at a turning point, both in Israel’s trajectory and in Jewish history more generally, and it’s exciting to be drawing comics during a time of upheaval and transition, even or especially if that upheaval causes anxiety in every other arena.

Just in the past five years you can see the tensions in the disparity between Obama and Netanyahu. Sure, there’s been a lot of disappointment in Obama on the left, but back in 2008 he captivated the imagination of a majority of American Jews in ways it’s hard to say for any other group aside from African Americans. Even if it wasn’t necessarily accurate, it’s how we perceived him: He was the outsider, he was an intellectual, he was motivated by social justice and universalism—that is, he was Jewish in a way that American Jews historically view ourselves. Meanwhile, who rose up in Israel? Benjamin Netanyahu, an anti-intellectual who stokes flames of racial incitement, anti-democratic hysteria, and xenophobia. So there’s this huge divide in the two dominant communities of Jewish life—but it’s complicated by the fact that American Jewish leadership, which has little in common politically, culturally, and religiously with their supposed constituents, genuflects before their prince on the other side of the ocean. There’s a seismic internal fissure between the values of the majority of Jews and this small subgroup that insists it knows what we really want and who we really are.

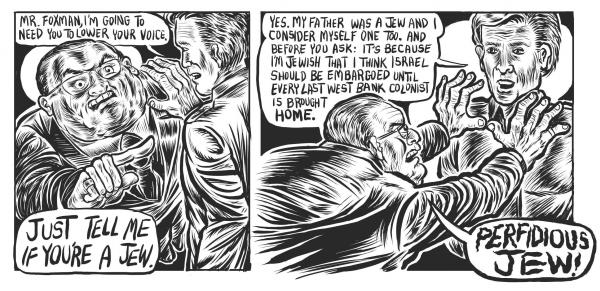

PB. That brings us to the next question: Politically, your assault upon neoconservatism and personalities like long-time ADL Director Abraham Foxman instantly recalls the cries of self-hating Jew or, for people like me writing along similar lines, “anti-Semite.” How do you deal with this nonsense?

EV. Honestly, if we define Judaism by the values and practices of the majority of American Jews, then Sheldon Adelson is virulently self-hating. Netanyahu can’t look in the mirror without grimacing in disgust. Abe Foxman cries himself to sleep in self-loathing revulsion. But we live in this inverted landscape, in which Jewish pride—pride in our secular traditions of humanism and universalism—is equated with self-hatred, and men like Adelson, Netanyahu, and Foxman can claim to be acting on behalf of all the Jews in the world.

I’m fascinated by the concept of self-hatred and how it’s used to police discourse, partly because it offers a grand psychology of the people doing the labeling. More than “hatred,” actually, I’m interested in the “self” side of the equation, because the labelers are really talking about the power to define the Jewish Self: who is a Jew and which Jewish values, cultures, and means of identification are legitimate.

If you love secular Jewish culture, Yiddish culture imbued with the humanistic and universalist values that were the bedrock of Jewish identity for generations and formed so much of European and American Jewish identity and politics, you’re likely to be called self-hating by the defenders of Jewish communal life today. That’s insane.

PB. Are your comics a way of creating or reflecting a new Jewish authenticity?

EV. My comics are satire of what’s going on. Really, there’s no such thing as Jewish authenticity. You can find textual support for social justice and for genocide. But when a minority of Jews claim to be legitimate and label others as self-hating, it’s offensive. Today, the flag of authenticity is waved most stridently by Orthodoxy and Zionism. So you can’t win: If you question either of those and say “Hey, Jewish values are something beyond segregation of women or segregation of Arabs,” then the “self-hatred” labelers insist you’re questioning yourself.

So I don’t know about “authenticity,” but it would be great if we dismantled or reappropriated the term “self-hatred.” Just recently, graffiti in Israel condemning a monumental new anti-democratic bill and warning of book burnings was called “anti-Semitic.” So to be anti-fascist makes you anti-Semitic? What’s “Semitic” then, fascism? Maybe in the minds of the labelers, which is why we need to stop letting them label things.

Or look at Jews for Jesus. They consider themselves to be fuller, more realized Jews, right? So in their eyes, I must be self-hating to reject Jesus as the Messiah. For me, when Orthodox or Zionist or Republican Jews claim to represent Jewish authenticity, it’s as ridiculous as claiming that Jews should get baptized and take communion in order to be authentic. I think we should take these terms back, or at least neutralize them. Or start calling Jewish Republicans “Jews for Jesus.” It doesn’t really advance the conversation, but it feels cathartic.

PB. You are wildly controversial and proud of it, but drawing for the Forward as well as left-leaning Israeli publications such as +972 Magazine, how do you do it? Ever get death threats?

EV. Sometimes there are ripples here and there, but mostly it’s confined to online comments, which I like to say should be read in tandem with the comics themselves—it becomes a text of internal commentary and argument, like a page of the Talmud if the Talmud were written by paranoid schizophrenics. More than individual comments, though, it’s troublesome when institutions or their representatives start shouting—like when the Anti-Defamation League applies pressure on Jewish communal media, or when the editor of Commentary calls me a “Kapo” and insists I not be published—that’s shadier than lone wolves on the internet, because it has the desired effect of silencing expression and limiting open, free-wheeling debate. And those forces are only getting louder and more empowered. But aside from all that, just from the perspective of self-interest, I don’t like being silenced.

PB. Artistically, you are in the finest Harvey Kurtzman tradition of what I call “immanent critique,” tearing apart shallow truisms by assault upon the revealing details. What other comic artists/editors have meant the most to you, and are they mostly Jewish?

EV. I love a range of writers and artists, some mostly for the art, some for the narrative, and some for both. I love the entire pre-code EC (Entertaining Comics) canon, including icons like Elder, Wood, Davis, Feldstein, Kamen, Krigstein, and Craig, but I also really like the non-EC titles because even though the art was less reliably solid, the narratives had no rules and sometimes went off the rails in amazing ways. Fletcher Hanks and Basil Wolverton are amazingly inspiring in art and narrative too. I’ve semi-recently gotten into Tarpé Mills’s “Miss Fury,” which I love for its camp and noir and insanity.

In terms of non-pre-code work, I love Robert Crumb, Julie Doucet, Charles Burns, and Rutu Modan. I’ve recently been reading Lisa Hanawalt, Simon Hanselmann, and Julia Gfrorer, and it’s great, funny and/or disturbing stuff. But most of the comics I end up reading are the pre-code 1950s stuff in collected form.* It’s largely available online but—especially when the colors are reproduced in a way that mimics the original pulp—I love the printed page.

PB. What about that old high-versus-low-art bugaboo that reached its apex with the New York intellectuals of the 1950s, Cold War liberals on the take (in the Congress of Cultural Freedom, and so on)? An old story but still one held up against “comics” of any kind. Aren’t you bashing the snobs by what you are doing? Is comic art an accepted art and do you think of it as an art?

EV. Comics and film are the highest art forms that exist. I don’t know whether comics are an “accepted” art—I guess maybe not yet, as every month seems to bring another headline along the lines of “Pow! Kablam! Comics—They’re Not for Kids Anymore.” In terms of the snobs, it’s hard to say—all culture merges into a stew, and I don’t think there’s much barrier behind “high” and “low” anymore. As for the Jewish content, I do think there’s a snobbery that favors the written word. Maybe that gives me more license as a visual artist, I don’t know. Boss Tweed allegedly said, referring to Thomas Nast’s cartoons, “My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!” The opposite might be true in the Jewish world. The people I satirize, yes they get upset, almost reflexively, but I’m not sure they understand the work. They don’t know how to read comics. It’s a foreign lexicon to them. They’re visually illiterate, and maybe that’s one reason comics drive them mad.

*The Comics Code Authority was established in 1954 as an alternative to government regulation of the comic book industry following Senate investigations and the publication of psychologist Frederic Wetham’s book Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comics on Today’s Youth. Approved comics received the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval, shown here. —Eds.

*The Comics Code Authority was established in 1954 as an alternative to government regulation of the comic book industry following Senate investigations and the publication of psychologist Frederic Wetham’s book Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comics on Today’s Youth. Approved comics received the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval, shown here. —Eds.

Leave a Reply