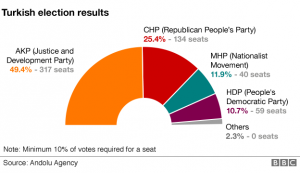

The November 2015 snap elections in Turkey have given back to the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) the parliamentary majority that it lost just a few months ago, in the June 2015 elections. However, the election results can neither resolve the crisis of Turkey’s authoritarian and neoliberal order, which is being challenged by the spirit of Gezi Park and new developments in the Kurdish movement nor obscure its complexity.

In the Prison Notebooks Antonio Gramsci describes a crisis as an “interregnum,” a period when “the old is dying and the new cannot be born,” and “morbid phenomena of the most varied kind come to pass.”[i] The morbid phenomena arise because the rulers lose their capacity to lead by consent and desperately attempt to re-assert their rule by using excessive force, what Gramsci calls domination. The rulers’ loss of capacity to lead, the approaching “death of the old,” needs to be viewed dialectically. It is the possibility of the new — although not-yet-become but can be foreseen — which causes the loss of consent, and pushes the rulers to exert coercion. And the bigger the threat of the new, the more ferocious are the attempts to contain it.

Such has been the nature of violence that preceded Turkey’s November 2015 elections. The June elections meant that the AKP lost its parliamentary majority for the first time; and should the opposition parties have founded a coalition, many who became victims of the violence could still be alive today—and the AKP could have been questioned for a few of its wrongdoings. But the old has been given another breath not only by the AKP but also by the ultranationalist Kemalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), and by the silent support of the anti-AKP Turkish public, thus allowing the state to continue its war against the Kurds. The latter has been reinforced by retaliation by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) that awoke dormant prejudices against the Kurds.

As the clashes between the PKK and the Turkish Army brought the Kurdish southeast back under exceptional rule (martial law), neither the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) nor the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) could have rallies. The AKP’s aim was clearly to evoke fear and terror in the eyes of the Turkish and Kurdish public that still has vivid memories of the violent 1990s. The disregard for the threat from the Islamic State (ISIS) also contributed to terror, with 108 people dying at a peace rally in Ankara in what became the deadliest terror attack in the history of Turkey. The November 2015 elections happened amidst this violence, handing back to the AKP its parliamentary majority. What the violence has shown, however, is the continuation and deepening of the crisis Turkey finds itself since the turn of the century and the crisis’s multi-layered nature.

The AKP as the First Popular Sign of the Crisis

Turkey’s crisis has first and foremost been political and pertained to the “representativeness” of the Kemalist foundations of the regime. The regime maintained its elitist and exclusionary configuration in its nationalist-conservative, hence seemingly populist, neoliberal form that was put into place following the 1980 military coup. The select few, who ran the state apparatuses, continued to exercise the most radical interpretations of Kemalism against the pious and ethnic groups, while those seeking representation continued to increase in the decades following the coup. The 1990s were a period of heavy conflict with the PKK and closures of various Kurdish and political Islamist parties by the Constitutional Court.

The situation was altered with the economic crisis of 2001, when public expenditure hit sky-high levels and the Turkish banking system collapsed. Given the high intensity of strikes during the 1990s — 1996 was the year with the highest worker participation to strikes in Turkey’s history[ii] — the need for transforming the hegemony to save Turkish neoliberalism became clearer.

The AKP emerged in the midst of this crisis. As an organic transformation of Turkish political Islam, it was first of all the representative of two groups seeking recognition from the regime: a religious capitalist class that was getting richer and a religious poor that was urbanizing during the 1990s. The former was ready to jump from the domestic markets to the global ones and the latter prepared to be more visible in public life. Thus, it challenged the regime on grounds of representativeness, anticipating its approaching death. Yet, to satisfy the needs of the first group and also to save Turkish neoliberalism, it has also been a neoliberal party unlike its predecessors in the political Islamist tradition. Eventually, the AKP acquired the new label required in the post-9/11 world, “moderate Islamist.”

The AKP’s Transformation and Its Limits

The AKP’s initial popularity and legitimacy in the eyes of most domestic and global critics of Kemalism show the depth of the Turkish regime’s crisis at the time. Yet, the party has essentially displaced Turkey’s crisis to the contours of a pragmatist representative democracy that was globally being questioned on the legitimacy of the Iraq War and by a nascent broad alter-globalization movement. It has continued to deepen the neoliberal reforms of the previous two decades in the country. In other words, the AKP may have challenged the hegemony in Turkey but it has sided with the hegemony globally. Its neoliberalism has always limited its democratization, and has relied heavily on state intervention to facilitate dispossessions of social, ecological, and urban commons in favor of capitalist classes. The party’s indifference to workplace deaths, which reached a total of 15,000 in its 12-year rule, is a case in point.[iii]

Even though the economic growth until 2007 rendered opposition to the AKP invisible, by 2008 the contradictions of the AKP as a supposed solution to Turkey’s crisis have become apparent for wider segments of society. The regime has transformed itself into an authoritarian neoliberalism, a natural development given the political soil in which the AKP grew and its response to the capitalist crisis of 2008.

The first source of this authoritarian neoliberalism is the AKP’s political Islamist roots, which much like any other ideology in modern Turkey’s history, grew out of the same soil as Kemalism. Behind its populist facade, it desires an equally, if not more, authoritarian and top-down control and full-deployment of state apparatuses, which should transform society. Nevertheless, the depth of conservative and nationalist ideologies in Turkish society means the AKP’s conservatism has acted partly like a mirror image of Kemalism, which was critical of society and aimed to transform it to resemble the “modern man.” The AKP has, instead, transformed the state to resemble the conservative and nationalist masses; filled with myths about national grandeur, religiosity, and an infamous culture of public shaming known as “neighborhood pressure” (mahalle baskısı). While this system is not representative, this community involvement provides the necessary illusion.

The second source of the AKP’s authoritarian neoliberalism is global. The 2008 economic crisis and the massive opposition to austerity politics that followed have exacerbated the authoritarian neoliberalism put into place following 9/11. The AKP, now feeling secure inside the state apparatus as the military’s influence had been minimized, yet also fearing that a halt to the economic growth since 2002 was imminent, dropped any democratization discourse and put the unitary, homogenizing logic of the Turkish State apparatus into motion. Backed by the AKP’s popular conservative ideology, this state apparatus was more than suitable for the global rise of authoritarian neoliberalism.

The AKP’s authoritarian neoliberalism has continuously revealed itself since 2008. Erdoğan urged the small shopkeepers to undertake their “traditional role” and keep the “neighborhood clean,” while the State kept its own “neighborhood” clean by pressuring journalists and incarcerating many. Everyday life and bodies would become targets of the regime. Erdoğan criticized popular TV shows for damaging Turkish values, compared abortion with murder, and continued his disparaging remarks about women.

All this happened as the economic growth proved unable to solve the unemployment problem in the country. The overall unemployment has been stuck at 11%, while unemployment for those between 15-29 has increased to a staggering 32%. By 2008 and onwards, the engine of the AKP’s economic growth was to turn Istanbul and other major cities into a “giant construction site,” entirely disregarding the environment and rural livelihoods.

The Gezi Uprising and the Nascent Opposition

The AKP’s balance sheet shows it has actually become the morbid interregnum that accompanies a crisis. In order to salvage its neoliberalism and guarantee its permanence, the party has appropriated the parts of Turkey’s regime that it deems useful for its conservative authoritarian neoliberalism, hence contradicting its democratization claims and constraining its representative capacities into much less than even a liberal democracy. As a result of the increasing repressiveness, the simmering opposition erupted with in a radical and unexpected form. The Gezi Uprising, despite its limited outcomes, proved that the possibility of the new has been alive in Turkey.

The characteristics of the participants were the uprising’s first novelty. The so-called silent, apolitical generations of the 1980s and 1990s took to the street. It is true that there were also activists in this generation, part of the alter-globalization movement influenced by Zapatismo and active in urban and ecological struggles. Yet, most had no prior political experience, and the activist strand had usually been sidelined by the centralizing logic of the hierarchical leftist parties of all sorts. The transformative potential of the uprising appeared, when the previously silent youth embraced the activist element’s politics.

The politics in the occupied Taksim Square and later in the neighborhood assemblies was reminiscent of the uprisings that had shaken the world in 2011. It was radically inclusive — as if all the old divisions in the country disappeared for a while, and radically democratic, horizontal, and autonomist — as if the dominant histories in Turkey have not been written by a homogenizing hierarchy in the left and right alike. In many ways, Gezi has brought the country’s radical politics to the present time, much like the AKP has brought its hegemonic politics in line with the global hegemony. Gezi has liberated Turkish radical politics from its esprit de sérieux, its Orthodox Marxism, democratized and popularized it.

Gezi defied definition by every dominant political organization in Turkey. However, it has also avoided defining itself, which might have made it possible to educate and mobilize some if not all of its constituents. The problem became more apparent as the uprising dissolved into hundreds of neighborhood assemblies. Almost every assembly had its own distinct definition of the Gezi depending on the socio-economic and/or ideological composition of the neighborhood. This discordance meant the new could not materialize out of Gezi, yet Gezi has undoubtedly altered Turkish politics in an unprecedented way.

The people’s experiences in the occupation of the Taksim Square and of some of the neighborhood assemblies generalized a new sensibility towards the country’s politics, one that sees the country’s problems are not only caused by the AKP’s conservatism and authoritarianism but are also related to the authoritarianism deeply rooted in Turkey’s political history as well as in neoliberalism. Notably, this new sensibility has found hope in inclusive, horizontal, and autonomist tendencies challenging the very foundations of the country. Through this new sensibility, a bridge between the younger populations in Western Turkey and a transforming Kurdish movement could be created, and so the HDP has appeared on the country’s political stage.

The Transformation of the Kurdish Movement and the HDP

The HDP is the latest reincarnation of the Kurdish movement’s political parties, organizations which had been shut down by the Constitutional Court. Yet, different from the past parties of the movement, the HDP clearly situates itself as a party for all peoples of Turkey. And in rallies before the June 2015 elections, the party’s co-president Selahattin Demirtaş acknowledged Gezi’s neighborhood assemblies and the city of Kobane as the inspiration of their “new life,” based on grassroots democracy, an outlook that positioned the party in line with the new left emerging in Europe such as Podemos and Syriza.[iv]

Overall, the HDP reflects the transformation of the Kurdish movement from Stalinist nationalism and secessionism to a radically democratic and autonomist political project dubbed “democratic confederalism” and represents its unification with the radically democratic sensibility that came out of Gezi. The most noteworthy example of democratic confederalism has been put into practice in Rojava by the Kurdish movement in Syria, whose fight against ISIS drew Western support, and also attention from notable leftist intellectuals, some of whom compares the political project to that of the Zapatistas. Yet, before Rojava Group of Communes in Kurdistan (KCK) undertook a similar effort in Turkey. The infamous reaction of the AKP government to the siege of Kobane, the state pressure to the KCK since 2009, and the heavy police response to the Gezi Uprising and the neighborhood assemblies prove the challenge put forth by these radically democratic projects to the authoritarian neoliberalism of the AKP regime but also show the difficulty of these projects to defend themselves without a defensive line inside the State. The HDP was born out of the hope generated by the Gezi Uprising to correspond to this necessity.

The Kurdish movement saw an unexpected ally in the Gezi Uprising, as well as a chance to legitimize its political project in the West of the country through a more popular alliance than what its usual leftist allies could offer. Leading individuals in the Kurdish movement praised Gezi for “breaking the hegemony,” defined it as “a message for democratic and new vision for Turkey” with which the Kurds should join forces, and assessed that “nothing can stay the same in Turkey after Gezi.”

Similarly, the grassroots forces in Gezi required a new bloodline because their first experiments in creating their own institutions through the neighborhood assemblies started to slow down by the end of 2014. Groups like On’dan Sonra and +1 organized mostly by people in neighborhood assemblies and in Western Turkey provided support to the HDP from below while preserving their autonomy from the party. Backed by such forces, the HDP has managed to become a hope for the country’s underrepresented as well as the younger generation in the West and the East, alike, overcoming prejudices against the Kurdish movement.

From June to November 2015: Crisis Intensifies

The violence inflicted upon the HDP prior to June elections and between June and November demonstrates the extent of the threat it has posed upon the old kept alive inside the morbidity of the AKP. Yet, electoral success of June and the necessary hope invested in the HDP have also concealed the contradictions of the Kurdish movement, which poses a challenge to the future of the party and the politics it promotes. For some in the Kurdish movement, the HDP appears to represent the “degeneration” of the Kurdish cause and the left. PKK’s leading cadres’ warning to the HDP to “get rid of the marginals in Cihangir” in August 2014 following Demirtaş’s promising results in the Presidential elections targeted the LGBTQ groups in the HDP, a manifestation of the PKK’s patriarchal and orthodox logic. Right after the June elections, the Group of Communities in Kuridstan (KCK) accused the HDP for wrongly suggesting to Öcalan that the call upon the PKK to give up the armed struggle, which, they argued, should be the decision of the PKK. What perhaps became the climax of the tense relationship between the HDP and older forces in the Kurdish movement was Demirtaş’s interview in the Financial Times in which he both invited the Turkish State and the PKK to an armistice and condemned the killings by the PKK. The PKK, however, played deaf to Demirtaş’s calls for a ceasefire, and it appears that the armed movement regards the HDP as subject to its control.

The PKK’s response to the state violence did not help the HDP, particularly, the killing of two police officers at their home by PKK’s urban forces on July 22, just two days after ISIS’s Suruç bombing that killed 33 people, thus legitimizing further action from the Turkish State. The AKP, using the incident to accuse the PKK of “unilaterally breaking the truce,” cultivated Turkish public’s fear of Kurdish separatism, which, the government claimed, was now “active not only in rural areas, but also in the cities” and “could kill police officers at their home.”

These instances suggest a deeper contradiction that overshadows the transformation of the Kurdish movement. The movement may articulate radical democracy, horizontality, and autonomism, but it has yet to provide a critique of the armed, hierarchical PKK and the idolized vanguard role of Öcalan’s which are incompatible with such politics. This situation adds another layer to Turkey’s crisis. The PKK and Öcalan’s persona feeds the hierarchical, centralizing logic of the Turkish State and the charismatic authority such a logic strives for, and vice versa. To address this deeper contradiction of the Kurdish movement is more critical at this juncture than the losses in the November elections.

What is to come?

At this point, without resorting to any short-term optimism, we should expect that the AKP will worsen its “morbidity” in the short term, as curfews and heavy military and police attacks over Kurdish towns, and the murder of the human rights lawyer and President of the Kurdish city of Diyarbakir Bar have already shown. Between June and November, the AKP has managed to consolidate a wartime power bloc that includes the entire political spectrum of Turkey’s strong state tradition. The attacks against the HDP and the Kurdish populace received support from the nationalist MHP, which has lost half of its voters to the AKP, and Kemalist nationalists, who seemed to be more concerned with the defense of the state than AKP’s anti-secularism for a change. Traditionally aligned with the CHP, the Kemalist Nationalists have recently been critical of the CHP’s softening towards Kurdish separatism with promises of increasing local autonomy and the selection of members who feel affinity to the Kurdish movement.[v]

The AKP also continues to reinforce unity through the possibility of an international war. The recent downing of a Russian plane is a case in point. This interregnum is likely to deploy all of its powers as it continues to intensify the authoritarian neoliberalism in responding to the economic crisis looming over Turkey and suppressing the opposition. Street thugs, pro-government civil society organizations that spread the AKP propaganda,[vi] a devoted police force, forced dispossession of the commons as well as opposition businesses, the reemergence of Turkey’s notorious “deep state,” and a daily religiosity that would try to infiltrate more and more into the daily lived experiences of Turkey’s society are likely to worsen the morbidity.

The global conjuncture also seems to work in favor of the Erdoğan regime as “a clash of barbarisms” that is no longer a distant possibility. The fears of radical terrorism and ISIS as well as a refugee influx generate another source of legitimacy for Turkey’s authoritarianism as it confronts the continuing crisis of capitalism. Accordingly, the EU officials have decided to restart negotiations with Turkey less than a month after the violence of the November elections, which comes in exchange of an agreement that allows the EU to return refugees, who used Turkey as their passage to EU countries. The AKP's risky actions towards Russia show its confidence in its Western allies.

Yet, the possibility of countering this development also remains alive because what a regime that is incapable of generating the single bit of consent from half of its people can do with violence will always be limited. The AKP’s weakness in creating a cultural hegemony had already been apparent during the Gezi Protests as the Party failed to exert any influence on the popular culture and technological savvy of the younger generations. The AKP and its authoritarian neoliberalism also have to deal with the inherent contradictions of neoliberalism, which promises individual liberties, all the while destroying the social fabric where such individually can gain meaning. The AKP’s destruction of the urban and rural commons is not only an economical dead-end but also a social one that will soon hit the poor classes among the AKP’s supporters.

It should also be noted that the HDP may have lost the conservative Kurds, but this saves the party from a “representational burden,” and its 10% in November elections shows it has consolidated much of its support in the West since the June elections. This consolidation also shows changed perceptions towards radical democracy and autonomism in the West of the country, despite how the Turkish state had associated these demands with the PKK and Kurdish separatism historically as well as recently during the June-November period.

Moreover, the opposition to the AKP outside the HDP is not entirely an oppositional position which only seeks to get rid of the AKP. The CHP’s internal democratization, opening towards the Kurdish cause, albeit limited and slow, is a demonstration of the latent influences of the new post-Gezi sensibility. The sooner the CHP can fight with the ghosts of its past, and pick its side in this crisis, the sooner it can serve as an immediate, although not permanent solution to the violence of the regime by seeking an alliance with the HDP.

Such a move could be beneficial in the short term for various reasons. It would create a broad democratic left bloc — whose leftism would undoubtedly come from the HDP but democracy can come from both parties given the authoritarianism of the present moment — to counter the AKP’s authoritarian statism. The HDP would then become more able to challenge the hierarchy of the PKK, and could also explain the similarities between “democratic confederalism” and the new sensibilities of Gezi, saparting the left from the shadows of the violence that concern many in the West. And finally, such a broad coalition could cultivate hope again against the risk of increasing apathy among the youth, who for a second time in two years witness their nascent dreams of change being crushed. While focusing on organizing—where the regime would feel the most damage in and around everyday life—is the most crucial step for the radical transformation of Turkey, such a broad coalition – although pragmatist – could provide the barrier against further regression of the people’s hopes amidst state violence.

Finally, there is the new that is waiting to born from the global crisis. The movements of 2011 continue their struggles, and despite failures, the hybrid parties combining autonomism and electoral politics such as the Podemos of Spain and the Syriza of Greece, or Barcelona in Comú and its role in the Guanyem citizens’ platform in Spain are examples to follow for the nascent new in Turkey’s radical politics.

In the end, the AKP may have extended the morbid interregnum by using the old repressive state apparatus and its constituents, but the crisis is nowhere near resolved. Should the opposition not accept defeat and continue organizing the new not only through political parties but also inside everyday life, which the AKP’s authoritarian neoliberalism would eventually target, the possibility remains of deepening the crisis of the old, preventing the consolidation of the authoritarian neoliberalism, and bringing to earth what may as well be a much more seasoned “Gezi Spirit.”

* Onur Kapdan is a PhD. candidate in Sociology and Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is from Istanbul, Turkey and his current research scrutinizes the aftermath of the 2013 Gezi Uprising in the country in relation to the global crisis between the autonomist and radically democratic tendencies that surfaced since 2011 and the authoritarian neoliberalism imposed since the capitalist crisis of 2008. He has written two pieces, published online, on the Gezi Uprising. The first was written at the beginning of the event ,“Reflections on Turkey’s Gezi Park Protests” and a later one followed during his field research in Turkey last year, as a silent solidarity against the police murders in the US was taking place, titled “Lonesome Corners, Where So Many Flowers Bloom Like Accidents.”

Contact: Kapdan@umail.ucsb.edu Twitter handle: @onurkapdan

[i] Antonio Gramsci. 1999. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Electric Books, p. 556.

[iii] One unforgettable incident is the Soma Coal Mine Massacre on May 13, 2014, in which 301 miners died due to the absence of legally required safety systems. In the face of the massacre, Erdoğan argued, “mine deaths were normal” and compared Soma with mining accidents in 19th century Britain, while one of Erdoğan’s consultants was kicking a protestor on the streets of Soma under police protection.

[v] See a series of columns from Yılmaz Özdil, a popular columnist among the nationalist Kemalists (ulusalci) since 2011 at the dailies Hürriyet and Sözcü such as his final column for the Hurriyet available here.

[vi] The Ottoman Hearths, Osmanli Ocaklari, has been the most visible of these prior to the elections. Moreover, as the state-supported violence targeted HDP offices across the country, and the PKK-Turkish State armistice came to an end pro-AKP NGOs, under a platform called “Civil Solidarity Platform” held a rally in Istanbul, which was framed as a “civil” reaction to terror. Yet, Erdoğan and Davutoğlu were the only political figures invited, and both gave speeches related to the November elections.

Leave a Reply