This is the first of three book reviews that will look at what Mexican intellectuals on the left have written in an attempt to understand Ayotzinapa and what it symbolizes and signifies for their country and its future. – DL

Sergio Aguayo. De Tlatelolco a Ayotzinapa: Las violencias del Estado. Editorial Ink, 2015. (This book in Spanish is available in several formats including Kindle, which is how the reviewer read it.)

The horrifying killing of six people and forced disappearance of 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College in the town of Iguala, Guerrero on September 26, 2014 had a dramatic impact on Mexico.

The disappearance and very probably the murder of so many young men, apparently with the collusion of a criminal gang and the police—and some believe the army—suddenly put faces on the terrible violence that had been taking place in Mexico since 2006. To date the Ayotzinapa killings have yet to be solved. The killers have not yet been identified and indicted. This is Mexico.

The violence in Mexico is really incomprehensible. Neither our reason nor our imaginations can hold before us in our minds the more than 164,000 killed, the 27,600 who have been disappeared, the countless numbers who have been injured, not to mention the hundreds of thousands who have been displaced. Then too there is the femicide, the targeting and murder of women that has become a pandemic in Mexico. All of this is accompanied by the impunity of the murderers and kidnappers, the government’s failed investigations, and the politicians’ evasion and deceit.

The violence continues to take place in a society where half the people live in poverty, where a fabulously wealthy oligarchy controls the government, and where American, European, and Asian corporations continue to make billions dollars in foreign direct investment, attracted by the low wages and state control over the labor force. All of the political parties are corrupt. The politicians are venal. The outlook is dim.

Sergio Aguayo – Tlatelolco and Ayotzinapa

Sergio Aguayo, a professor at El Colegio de México and Harvard Univesity has written a number of books dealing with the issues of human rights, nationalism, politics, and the intelligence services in Mexico. He was in the 1990s a leading figure in the civil society movement working with other groups to win free and fair elections and he continues to speak out on human rights, as he has in this book. If he were an American, Aguayo would be described as a liberal—though that category that doesn’t really exist in Mexico—a man who would reform institutions.

He writes in the introduction that the Mexican state has to be held primarily responsible for the continuing violence in his country, that the Ayotzinapa kidnappings demonstrate organized crime has created a parallel state, and that the Mexican people will have to organize themselves to take back their government and insure legality.

While Ayotzinapa appears in the title and is discussed in the last chapter, this seems to be a book principally about the Tlatelolco massacre of 1968 that Aguayo had been working on for some time and apparently decided to publish last year because of the Ayotzinapa events. So some readers may be disappointed, and justifiably, for though they will find a meticulously researched and annotated account of the Tlatelolco, they will be unsatisfied by a very thin and weak account of the period from 1968 to today, and virtually nothing of interest on the Ayotzinapa disappearances.

The Democracy Movement of 1968

Aguayo’s account of Tlatelolco provides an impressive description of the breadth of the pro-democracy movement of 1968 that had sprung up not only among students, but also among working class and middle class people, and not just in Mexico City but throughout the country. Many students were influenced by Pablo González whose book Democracy in Mexico (1965) who criticized the Mexican state but argued against violence.[1] Though most activists were committed to militant but peaceful protest, a small fringe contemplated violence. Carlos Fuentes’ Paris: The May Revolution (1968), about the massive May-June strikes in France, suggested that an initially peaceful movement might take to the barricades described and pictured in his book.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 influenced some Mexican youth, though they failed to appreciate the actual relationship between the Cuban and Mexican governments. As Aguayo writes:

We knew that the United States supported the Institutional Revolutionary Party regime unconditionally; the terrible mistake was the inability—authentic in some, simulated by others—to recognize that the government of the Soviet Union and Cuba formed part of the foreign legion, of the Praetorian Guard, dedicated to protecting the government of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. Our heroes were the partners of our oppressors. [My translation – DL.]

The government, working closely with the news media that it controlled, had to “fabricate an enemy,” as Aguayo puts it. So the claims were made that the students and others involved were privileged ingrates, that they were ingenuous idealists, that they were dupes of the Communists—Russian, Cuban, or Chinese—or that they were tools of the United States. They were called anti-Patriotic, traitors. In his memoir the president called them “bloodsucking parasites.”

The Government Against the People

The Mexican government carried out what Aguayo calls a “general offensive” aimed at separating the students and other movement activists from other sectors of society, but particularly from the working class. Aguayo writes,

They vaccinated union workers with “hundreds of meetings” in which they presented “the government version of the facts” and in the factories they created “permanent groups to prevent student incursions.” (My trans. DL)

The author argues that various branches of the Mexican state—President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz; Luis Echeverría, the Minister of the Interior; Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, head of the secret police; and the generals Luis Gutiérrez Oropez and Mareclino García Barragán—each had different understandings, misunderstandings, and conflicting objectives in attacking the movement, none of which excuse them, since they all intended to violently suppress it. The president wanted the movement crushed before the Olympic Games being held in Mexico City within a week. Minister of the Interior and future president Echeverría had promised the U.S. Embassy that they would end the student agitation before the games.

President Díaz Ordaz told Javier Barros Sierra, rector of the University that he would end the conflict between the democratic movement and the government peacefully. But that was just a political maneuver, as cover for the unleashing of the military on October 2, 1968. The last demonstration by the democratic student and civic movement numbered about 8,000 people who believed that the government was finally going to sit down and negotiate with them—but the government sent between 5,000 and 10,000 soldiers to crush them. Hundreds were killed in the confusing assault—most today believe around 300. The leaders of the movement were taken to Military Camp #1, the cadavers removed, the wounded taken away. The sidewalks scrubbed to wasy away the blood.

Aguayo holds Díaz Ordaz to be absolutely responsible for the Tlatelolco Massacre, which, Aguayo argues was similar to another that the president had ordered in San Luis Potosí in 1961 when he was the Minister of the Interior in the administration of Adolfo López Mateos.[2]

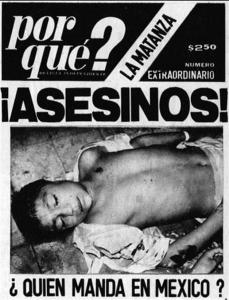

While the magazine Por Que? brought out a special addition with photos of wounded and dead students, most of the press and the other media gave out the government’s story that sharpshooters had fired at the Mexican Army. In fact, there were sharpshooters, but they were also part of the Mexican Army. The government asserted that only seven people had been killed, a preposterous claim given the photos that had been published abroad. The United States and England, the Soviet Union and Cuba all cooperated with Mexico, working to suppress any actual account of the events. Yet the government and its media failed to put forward a very convincing story, because, as Aguayo writes, it didn’t understand that in history the account is as important as the bullets.

Where there was a free press the foreign media told the truth: The New York Times wrote that “federal troops fired rifles and machine guns at a peaceful student demonstration.” Le Monde likewise reported that “the army and police opened fire without warnng,” saying as well, “it was a massacre: there exists no other word to describe what has happened in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas.” The Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, was wounded by a bullet and robbed of her money and watch by a cop, wrote vivid, veridical accounts of the massacre, making her a hated enemy of the Mexican government.

Still governmental officials and most of the country’s major intellectuals defended the government’s version of events, the cowardly attack on the soldiers by the dupes of foreign powers. Even the beloved and esteemed former president Lázaro Cárdenas rallied to the ruling party he had helped to create and affirmed the government’s official story, helping to win over the national and international left.

Anywhere in the country that the democratic movement raised its head, a demonstration or a march, the police and the army moved in. Hundreds were arrested. Everywhere in the world, the Mexican government attempted to quash its critics. Virtually no Mexican official spoke out. The exception was the writer and poet Octavio Paz, at the time Mexican Ambassador to India. Paz resigned his position in India, calling Tlatelolco “an act of State terrorism pure and simple.”

Beginning in 1969 a number of intellectuals began to tell the story of what actually happened: Julio Scherer García, director of Excelsior; Ramón Ramírez in El movimiento estudiantil de Mexico, Octavio Paz in Posdata; writesr Carlos Monsiváis, Carlos Fuentes, y Elena Poniatowska, Jacinto Rodríguez Mungía, Kate Doyle and Susana Zavala.

Tlatelolco to Ayotzinapa

Aguayo devotes the last chapter of his book to the path from Tlatelolco to Ayotzinapa. He creates a periodization of repression in Mexico. The first period lasts from November 1969 to August 1985. During this period President Luis Echeverría Álvarez both create a political democratic opening while also continuing to engage in the violent repression of government opponents. Aguayo mentions but does not explain or detail the “dirty war” of the 1970s during which the government disappeared some 500 left activists, many of them from armed leftist guerrilla groups.

Aguayo’s second period goes form 1981 – 2000 (the second set of dates don’t line up with the first), during which he argues that the Mexican Army refused to continue to be used for repression of the civilian population without express conditions. The Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado government closed down the Federal Security Administration (LaDFS), an organization that operated with impunity while its agents enriched themselves, says Aguayo. This came as the result of the agency having kidnapped and murdered a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency agent in February of 1985. LaDFS was shut down, but its corrupt agents were not prosecuted and many went off taking their talents to the country’s criminal organizations.

The financial crises of the 1980s and 1990s debilitated the state, and at the same time the presidentialist system began to weaken partly as a result of political reform. The North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994 led to the Chiapas Rebellion led by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), another indication that the state as the only legitimate source of violence was weakening. Aguayo suggests that the drug deals followed the EZLN’s example or at least acted similarly, establishing regional redoubts beyond government control. This led in the end to what he sees as the development of two states: one headed by President Enrique Peña Nieto and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the other headed by organized crime.

Aguayo says that both President Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderón missed opportunities to right the ship of state. Fox promised a “Truth Commission” to look into past abuses, but then gave up the idea. Calderón, writes Aguayo, “…had the courage and the wisdom to throw himself against organized crime. But he lacked will, information, temperament, and compassion with the victims.” And, “he was indifferent to the cost in human lives.”

Peña Nieto, says Aguayo, began by professionalizing the security forces, improving coordination between them, and putting emphasis on prevention. But then came the typical weaknesses of the government. “His government has not recognized the magnitude of the challenge lacks a coherent national and regional policy that attacks the root of the problem, and shows great indifference to the cost in human lives.” Aguayo then spends a few pages on Ayotzinapa, offering nothing of significance.

Aguayo’s account of the period from 1968 to 2015, really more an outline than a narrative or analysis, is extremely disappointing, and not only because it is so thin. It is also clear that Aguayo, despite write that the Mexican people will have to create a just society, really looks to the state to reform itself. This is clear from his comments about Fox, Calderón, and Peña Nieto, in each of whom he at first saw some hope of change. Aguayo’s liberal outlook looking for change through the system, rather than changing the system is the fundamental weakness of this book.

[1] I have to admit that took the title of Pablo González’s book for my own, Democracy in Mexico (1995). Under international law titles cannot be copyrighted. I only wish my book had had the success of González’s.

[2] Aguayo had made this argument earlier in his book La Charola: Una historia de los servicios de inteligencia en México (Mexico: Grijalbo, 2001), pp. 135-36.

Leave a Reply