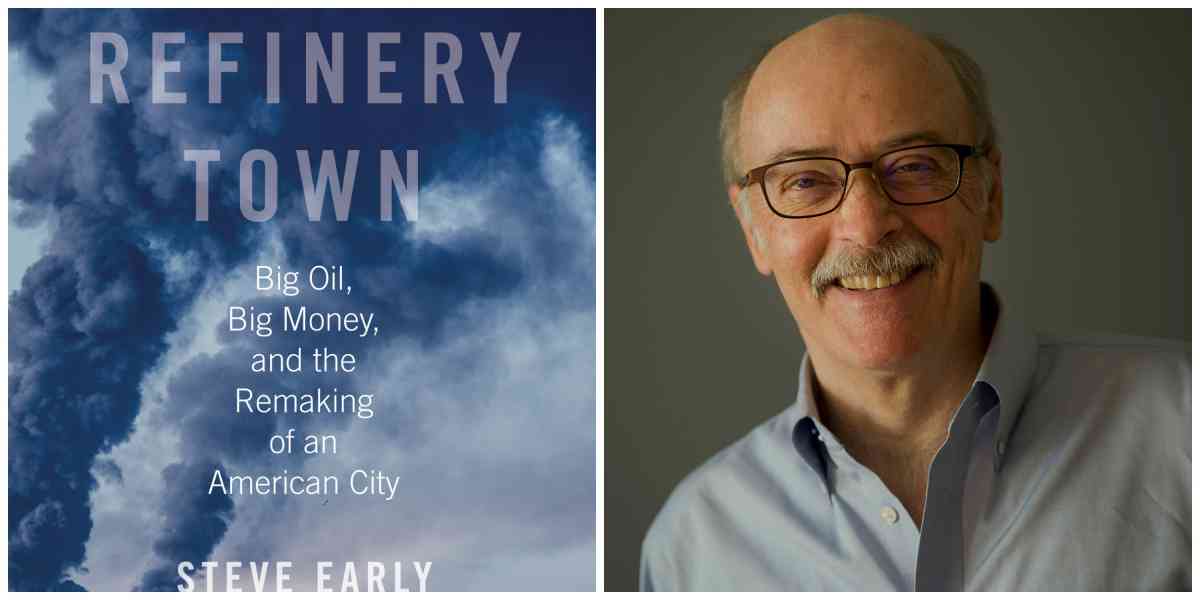

Mohsen Abdelmoumen: You have written a book about the city of Richmond, California, where you live, prefaced by Senator Bernie Sanders: Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City. This book shows us the experience of this city that has won struggles such as raise the local minimum wage, defeat a casino development project, challenge home foreclosures and evictions, and seek fair taxation of Big Oil and Big Soda. Can we say that the Richmond experience should inspire progressive activists in other cities around the world?

Steve Early: The struggle to revitalize and democratize Richmond, CA, a multi-racial, working class city of 110,000 near San Francisco, is part of a larger municipal reform trend in the U.S. This current emerged during a period of political deadlock at the state and federal level during the Obama Administration.

Under Donald Trump, we’ve gone from bad to worse, forcing progressive city hall leaders to deploy the limited resources of local government to fight poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation because government at higher levels is failing to address such problems or, in the Trump era, making them worse.

In other countries, there is a similar trend toward “going local”—for example, left-wing mayors and city council members have been elected in cities like Barcelona and Madrid, on a similar program of promoting direct citizen participation in municipal affairs.

In electoral politics at the national level in the U.S., those with the most donor clout—what Bernie Sanders calls “the billionaire class”—are well positioned to win, whether their preferred presidential candidate comes in first or second.

The longer-term success of current grassroots “resistance” to Trump depends on building a broader organizational base for the U.S. left in local politics, labor organizing, and social movement building. “What we need,” Sanders argues, “is a 50-state strategy, which engages people—young and working class people—to stand up and run for school board, to run for city council, and the state legislature, so government, at all levels, starts listening to ordinary people instead of campaign contributors.”

“Taking over city hall in Richmond or any other city won’t, by itself, keep big money out of politics,” Sanders points out. “It can’t stop climate change, eliminate economic injustice and racism, or stop all law enforcement abuses. Addressing those problems requires broader movement building, national and global in scale.” But “rebel cities” are one key place where that movement building can develop and become stronger.

According to you, doesn’t the fight against big capital pass today by local struggles against multinationals, banks, etc.? Isn’t there a need to reinvent the struggle?

I think progressives today are not so much re-inventing this struggle as reviving a political tradition and organizing strategy more than a century old.

Before World War I, we had a mass-based Socialist Party in our country that boasted nearly one hundred thousand dues paying members. It grew in part through labor militancy but also by challenging local business interests for control of city hall.

Socialist mayors were elected in seventy-five cities in twenty-four states. Overall, about twelve hundred socialists served in public office and used their municipal positions to improve services for workers and the poor, including public housing, sanitation, and street repair. They also encroached on the private market by taking over local power and water companies and making them publicly owned utilities, some of which survive to this day.

These left-wing gains were reversed when the U.S. government cracked down on socialists opposed to military conscription and US participation in the imperialist slaughterhouse of World War I.

To curb radical influence at the local level, many cities, like Richmond, also switched to a city manager form of government. The number of elected, full-time mayors, whether socialist or not, was reduced throughout the nation. More city council members became part-time, were elected at large, citywide (rather than from their own working class neighborhoods) and, in office, were limited to setting general policies carried out by trained, business-oriented professionals.

Only after the movements of the 1960s, did U.S. radicals begin regaining ground in local politics—first, in university towns like Berkeley and Santa Cruz, CA., Madison, Wisconsin, and Burlington, Vermont. Socialist Alternative city councilor Kshama Sawant in Seattle, Richmond’s two-term Green Mayor Gayle McLaughlin, black radical mayor Chokwe Antar in Jackson, Miss. and many others like them represent a more recent and larger wave of left-wing insurgents.

What they all have in common today is a commitment to challenging corporate power—and the corporate Democrats and conservative Republicans who are its equally dutiful servants.

From what I read about you, you advocate an original idea, namely to organize struggles at the local level, in particular by structuring the progressive forces at the city level, and then build a large national movement. For you, are local struggles necessary as a first step towards a general change?

I don’t want to make too much of a virtue out of the momentary necessity of “municipalism.” One way that progressives in Richmond have responded to Trump’s election last Fall is by joining forces with like-minded former Bernie supporters in the post-Sanders campaign network known as Our Revolution (OR).

In November 2016, Our Revolution helped raised thousands of dollars for the two city council candidates backed by the Richmond Progressive Alliance. Both won seats on the council, giving it a RPA “super-majority” of five out of seven members.

If OR is going to achieve its full potential as a force for change inside or outside the Democratic Party, it will need two, three, many local groups like the RPA’s or the Vermont Progressive Party, the very successful third party formation in Vermont inspired by Sanders own career in the state.

The RPA voted to formally affiliated with OR in January and is now doing outreach to other like-minded local groups in California. Richmond progressives know they have to become part of a broader progressive movement to defend past municipal gains and make real change at levels of government higher than Richmond city hall. So one founder of the RPA, former Richmond mayor Gayle McLaughlin is running for Lieutenant Governor of California as a progressive independent; vice-mayor Jovanka Beckles is campaigning, with RPA support, as a “corporate free” candidate for the state legislature.

In your book The Civil Wars in US Labor: Birth of a New Workers’ Movement of Death Throes of the Old, you put your finger on the wound by showing the shortcomings of the American union movement which, instead of defending the interests of the workers, has lost itself in internal struggles which are prejudicial to the workers’ struggle. Can we say that we must reform or radically change the functioning of the American union movement?

In the early 1950s, nearly of third of the U.S. workforce was unionized. Today, that’s down to less than 7% in private industry and 12% overall.

Until recently, union militants here often made a distinction between “external organizing”—the process of recruiting workers currently lacking collective bargaining rights—and “internal organizing.” The latter refers to shop floor efforts among existing union members aimed at strengthening their collective agreements with employers through workplace mobilization activity, including strikes or other protests on the job.

This distinction doesn’t exist, of course, in many other countries, like France, where union membership is voluntary, more fluid, and multiple unions compete and/or cooperate in the same workplace or enterprise. Building organizational strength in a workplace, new or old, where there is little or no union presence requires the same kind of one-on-one recruitment of co-workers, followed by displays of solidarity.

In the U.S., as a result of mounting legal and political setbacks, virtually all labor organizations now face the same challenge as French unions. Throughout the country, right-wing forces have made it harder for unions to secure financial support from the 14.6 million workers they still represent in the private and public sector. To survive, much less succeed, in this new workplace environment, unions must return to their roots and begin to function again like they did before passage of the 81-year old Wagner Act, the federal law enacted under the pressure of left-led industrial union organizing in the 1930s.

One downside of the Wagner Act model was making unionization too much of an “all or nothing” phenomena; if an organized minority of workers tried to act collectively in an otherwise “non-union” workplace, management was not legally obliged to address their demands and, very often, unions provided little sustained backing for the shop-floor activity of non-dues payers.

In addition, federal labor law in the U.S. greatly favors incumbent unions, which means it’s much too difficult for workers to switch from one union to another, if they are dissatisfied with their workplace representation and support. Once insulated from the threat of membership defection, U.S. union officials became much too free to ignore rank-and-file complaints and problems, while promoting, in some industries, labor-management “partnerships” of questionable value to workers.

Doesn’t your essential book Save our Unions: Dispatches from A Movement in Distress call for a re-founding of the trade union movement for more combativeness and efficiency in order to defend the interests of the working class against big capital?

There is a now nearly 40-year old network of labor activists in the US that has promoted such a “re-founding” through the vehicle of Labor Notes.

Along with others from my union, I have been a longtime time Labor Notes supporter. It functions as an independent, rank-and-file oriented labor education project producing a monthly newsletter and holding local, regional, and national training sessions which promote greater union democracy and militancy to better defend the interests of workers against big capital.

The next Labor Notes conference—attended in recent years by more than 2,000 trade unionists, from the U.S. and abroad—will be held in Chicago, on April 6 to 8. For more information, see here. There’s no better crowd to be part of, if you want to put “the movement back in the labor movement.”

Embedded with Organised Labour: Journalistic Reflections on the Class War at Home goes over the history of the union movement in the USA and how it has been able to crystallize the struggles of the working class in the past. In your opinion, can we say that the labor movement must learn the lesson of its past experiences in order to be efficient? Is there a need to give a new impetus to the trade union movement?

The increasingly defensive battles of U.S. workers suggest that a new model of union functioning is both possible and necessary for labor movement survival. As more unions come under attack, rank-and-file members are realizing they can’t just be passive consumers of union services. In workplaces lacking “union security” or formal collective bargaining, workers themselves are taking greater leadership and initiative, while depending far less on full-time officials and staff.

Throughout the U.S., it will take far wider and more concerted worker mobilization for “organized labor” to remain “organized” without the state or federal legal protections of the past. In politics, as well as on the job, it’s time for new directions and less dependence on Democrats who have been largely useless in the fight against union busting and resulting open shop conditions.

In Democratic presidential primary voting during the spring of 2016, many labor militants were among the 13 million Americans who cast their ballots for the most pro-worker member of the U.S. Congress and its only socialist—Senator Bernie Sanders from Vermont.

Sanders left-wing electoral insurgency has attracted support from disillusioned Democrats, independents, and even some working class Republicans. By focusing attention on “billionaire class” domination of both major political parties, Sanders’ grassroots campaign fostered long-overdue debate and discussion among labor militants about the need for union transformation—in the workplace, the community, and politics too.

The national network that some of us helped form to assist his campaign—known as “Labor for Bernie”—has morphed into a group called “Labor for Our Revolution.” In the six or seven national unions that backed Bernie and the far greater number of AFL-CIO affiliates that settled for Hillary Clinton, there is continuing questioning of labor’s past approach to politics.

You have a long experience in the union movement, especially in the Communications Workers of America (CWA). What can you tell us about your experience with this organization?

I’m proud to report that the union I’ve belonged to for 37 years was the largest in the U.S. to support Sanders for president. When I first went to work for CWA in 1980, it was not the type of union to endorse a Jewish socialist atheist, former anti-war activist who’s never been a Democrat.

So that’s one sign of change within labor right there. It reflects, in CWA’s case, a broadening of the union’s membership based over the last four decades. What began as an enterprise-based union within the telephone industry—composed almost entirely of telecom workers—is now a far more diverse, amalgamated organization of private and public sector workers, white collar and blue collar employees, with members in manufacturing, the media, higher education, health care, and the airlines.

That greater diversity has contributed to greater political pluralism and support for progressive politics.

In your opinion, can we appeal for the establishment of a union front on the global level to counter global neoliberalism and imperialism?

Globalization, corporate restructuring, deregulation or privatization, and myriad forms of outsourcing have created new workplace terrain that’s distinctly unfavorable for workers, in the U.S. and many other countries. Labor organizations, rooted in a single nation-state, have been forced to re-think their organizing and bargaining strategies, and how they’re structured.

More have come to realize the importance of cross-border solidarity and international union ties. My own union, CWA has invested a lot of resources in sustaining relationships with like-minded labor organizations in Canada, Mexico, Germany, and other countries where we deal with common employers, like T-Mobile, the cellular phone service provider.

The workers of the world do need to unite, as a famous 19th century radical economist once argued. And, fortunately, in the 21st century, we have a lot more tools for faster communication, better information, and closer coordination of union action on a cross-border basis. The challenge, of course, is making sure those linkages actually do involve workers themselves, as opposed to just the labor officialdom.

Don’t you think that a corrupt union is the best ally of the ruling classes?

In a country lacking any statutory entitlement to universal health insurance, pensions, vacations, or other paid time off, collective bargaining still makes a big difference in the lives of 16 million people. Union contracts spell out wages, employment conditions, “fringe benefits,” and a procedure for contesting unfair discipline; most non-union workers have nothing like it and powerful employers are free to dictate terms of employment, as they see fit. Or redefine the nature of employment, leaving millions of people mistreated and exploited as casualized labor in all its various forms.

Whenever unions themselves are guilty of organizational misbehavior—particularly in the form of leadership involvement in financial corruption—that greatly undermines and discredits the idea that collective action is absolutely necessary for workplace improvements and improving working class living standards.

So, in that sense, a corrupt union is an ally of the corporate ruling class in its never-ending fight to reduce union influence in the U.S.

Don’t you believe that capitalist society and its mode of consumption only lead to the alienation of the dominated classes?

I’m not much of a theorist but that formulation sounds right to me.

Can humanity survive another capitalist century?

I’m not a futurologist, but if I was, I would say the future does not look good, for planetary survival, after another capitalist century.

Are not the reformers of the capitalist system sellers of the mirage and the dream? In your opinion, can the capitalist system be reformed?

To save the planet from the devastating human and environmental impact of climate change is going to take more than “reform” of the system. There have always been lots of reasons—worker exploitation, imperialism, war, et al.—to replace capitalism with something better. Global warming, rising sea levels, extreme weather leading to drought, famine, fires, and/or flooding, plus animal species extinction, provide an over-arching rationale for fundamental economic change.

You are both a man of action and a man of theory and your career is very rich and atypical: labor activist, journalist, author, lawyer, you serve on the editorial advisory committees for four labor-related publications—Labor Notes, New Labor Forum, WorkingUSA and Social Policy, you are a member of the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA) in your city and you are involved in struggles within the local community. For you, as a modern leftist and trade unionist, is it a necessity to be at one and the same time on several fronts?

In Richmond, as I describe in Refinery Town, there’s a lot of overlap and inter-connection between labor, community, and environmental issues—so it’s a good place to be remain involved in union solidarity, while becoming more active in local campaigns for environmental and economic justice.

Originally posted at the American Herald Tribune.

Leave a Reply