In recent years Greece has come to exemplify the attempt of capitalist elites to respond to the global capitalist crisis through an attack on the rights and living standards of workers and ordinary citizens around the world. As the brutality of this attack has been nowhere as pronounced as it is in Greece and as it has understandably given rise to a strong (though not strong enough up to this point) popular response, Greece has received a lot of attention from capitalists, workers, and concerned citizens the world over.

In recent years Greece has come to exemplify the attempt of capitalist elites to respond to the global capitalist crisis through an attack on the rights and living standards of workers and ordinary citizens around the world. As the brutality of this attack has been nowhere as pronounced as it is in Greece and as it has understandably given rise to a strong (though not strong enough up to this point) popular response, Greece has received a lot of attention from capitalists, workers, and concerned citizens the world over.

The importance of Greece as a test case for the attempt to solve neoliberalism’s crisis by entrenching the neoliberal model even further is amplified by the historic presence in Greece of a strong Left, with a long tradition of militant social struggles. This history suggests that if capitalist elites get away with imposing shock therapy as the response to the current crisis in Greece, there is no reason why they cannot follow the same recipe everywhere else.

In fact, they have started to do so, both in Europe and beyond. And, as they do so, other European countries are increasingly coming to realize that Greece is their future, if the austerity programs imposed on them are allowed to run their natural course. Country after country in the European periphery finds itself in a deepening recession, with unemployment rates breaking one record after another and young people beginning to migrate in droves. This social devastation is, however, also accompanied by mounting resistance. By now, anti-austerity resistance is mounting around the Southern European periphery, encompassing even countries, like Portugal, which until recently were portrayed by mainstream media as being much more stoic in the face of austerity than Greece. In short, Europe and the world are faced with the prospect of prolonged social and class conflict. It is the outcome of this conflict that will determine the way the current crisis is resolved.

To understand the state of the struggle in Greece today, some background may be helpful. As far as its position in the international division of labor is concerned, Greece is a country of the semi-periphery. As such, it went through a process of industrialization before its neighbors in the Balkans but after the countries of Western Europe. This special position of Greece within the world capitalist system accounts for two of the specificities of its class structure and history.

First of all, Greece is characterized by a long history of indebtedness dating back to the 19th century and the loans Greece took to finance the struggle of independence from the Ottoman empire. This history of indebtedness, which has for over a century accompanied the effort of capitalist elites to "modernize" the country, is not surprisingly also a history of periodic insolvency and loss of national sovereignty.

Secondly, Greece has long been characterized by a class structure that is not fully capitalist. Indeed, until recently the percentage of the population that was self-employed, living off small businesses, etc., was much larger than in most advanced capitalist countries. In fact, one of the effects of the current austerity program is to destroy tens of thousands of these businesses and to lead to a greater concentration of capital. This development obviously benefits large capitalist businesses, both domestic ones and foreign ones, looking to gain from the massive and brutal restructuring of Greek society. In this sense, the Greek austerity program is a vast experiment in the dispossession and proletarianization of Greek society’s middle strata.

In any case, however incomplete and flawed Greece’s industrialization and adoption of the capitalist model may have been, it generated, from early on, intense social and economic struggles and the development of a strong political left. These struggles have often been met with state repression that has at times, such as in the 1930s and between 1967 and 1974, even taken the form of military coups and a suspension of the trappings of bourgeois democracy.

One important moment that has long shaped the country’s political life and social struggles alike was the civil war that erupted soon after the end of Nazi occupation in 1944. During the war, the Greek Communist party and the Greek left more generally played a leading role in the development of a strong anti-Nazi resistance movement. Because of its role in the resistance, the Greek left saw its power and prestige grow, a development that was seen as a threat by Britain and the United States, which intervened after the war to make sure that the left would not take power. In fact, it is to Greece that we owe the dubious honor of having inspired the Truman doctrine.

Having asserted its control over Greece immediately after the war, the US remained a dominating presence for decades. In fact, the post-war period was one of parliamentary authoritarianism and a persecution of the left, culminating in another right-wing coup in 1967. The military regime installed by this coup lasted until 1974. It was only in 1974 that political conditions in Greece normalized, bringing that country closer to the realities of other capitalist democracies. For example, the Communist Party was no longer illegal and it became possible for other forces on the left end of the political spectrum to organize in the open.

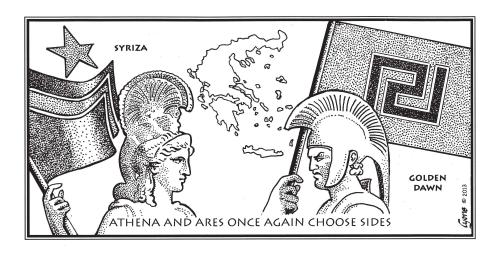

The legacy of the civil war and the period up to 1974 has had a strong polarizing effect in Greek politics, an effect that persists, while taking ever new forms. In the 1980s, this effect was expressed as a rivalry between the Socialist and conservative parties. Most recently, as socialists and conservatives have become political allies faithfully administering the brutal austerity policies favored by Greek and European capitalist elites, anti-communist rhetoric has been revived and reserved for the rising anti-austerity party of the left, Syriza (which is the Greek acronym for Coalition of the Radical Left).

In any case, the end of military dictatorship saw an intensification of class struggle and a strengthening of the labor movement. At least as important, however, were the youth and student movements. In fact, it was a peaceful student revolt in November, 1973 that paved the road to the collapse of the military regime. Although the regime brutally suppressed this revolt, killing dozens of students and young protesters, it was seriously weakened in the process. By the summer of 1974, and under the additional blow of Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus, the military regime was history.

The strengthening of the Greek left and Greek social movements was able to produce important gains for Greek workers and citizens once the military dictatorship came to an end. It also contributed to the coming to power of the Greek "socialist" party in 1981. This party rose to power by combining a left social democratic platform, with respect to domestic policy, with a left nationalist discourse that lambasted the historic subordination of Greece to the United States.

To begin with, the rise of the socialists was accompanied by rising salaries in the public and private sector and by the establishment of a rudimentary welfare state. As the building of this welfare state was not, however, accompanied by a corresponding rise in the taxation of Greek businesses and the rich, it was financed by borrowing that led to a growing public debt.

At the same time, the Greek economy was weakened both by the effects of the structural economic crisis of the 1970s and by the effects of its growing economic integration within Europe. As the recent European crisis has made clear, most of the benefits of European economic integration have gone to the economically stronger countries of the European North, such as Germany, which gained greater access to the markets of the South. Meanwhile, the productive capacity of weaker countries, like Greece, was wiped out.

In particular, a process of deindustrialization set in. This process was aggravated by the collapse of Communism, which led many businesses to close their plants in northern Greece and reopen them in neighboring low-wage countries, such as Bulgaria.

Even before Communism collapsed, however, Greece had started to align itself with the rightward turn that many other countries in Europe and the world experienced after the crisis of the 1970s signaled the end of the post-war golden age of regulated capitalism. Indeed, by the mid-1980s the Greek "socialists" had begun their move to the right, inaugurating a neoliberal restructuring of Greek society. Slow at first, this process of neoliberal restructuring has proceeded at a breath-taking pace since Greece turned in 2010 to Europe and the International Monetary Fund for loans that allowed it to continue servicing its debt.

The implementation of neoliberal policies, through the alternation of "socialist" and conservative governments at first, and through a coalition government between them by now, has been as disastrous in Greece as it was in other parts of the world. These policies have led to growing economic inequality, lower business taxes that contributed to rising deficits, and more flexible labor relations that drastically increased the numbers of precarious workers, especially among the young.

These grim realities were for a time obscured by a false sense of prosperity prevailing among large segments of the population immediately after Greece entered the eurozone about 10 years ago. Greece now enjoyed easy access to low-cost credit. At a time when the breakup of the eurozone seemed inconceivable, its participation in the exclusive euro club meant that, as far as financial markets were concerned, Greece and the European south were almost as safe as Germany and the countries of the European North.

Not surprisingly, access to cheap credit, in conjunction with the real estate and construction bubble associated with the preparation for the 2004 Olympics, produced a period of high growth rates. This growth was not accompanied by a significant improvement in Greece’s finances, so when the global capitalist crisis erupted, Greece, like other European countries, saw its tax revenues shrink, its access to credit curtailed and its budget deficit increase both because of the fiscal effects of the crisis and because of the need to bail out its financial sector.

Interestingly, however, Greece experienced serious social turmoil even before it had felt the full impact of the global crisis. Indeed, the murder of an unarmed teenager by a police officer in December, 2008 triggered a major youth revolt that mobilized large and varied sectors of the population for weeks, thus leaving the conservative government in power at that time seriously weakened. Although this major upheaval can, in retrospect, be explained by reference to the bleak future that young Greeks were already facing at that time, this revolt caught everybody, including the Greek left, by surprise.

One of the remarkable features of the December, 2008 revolt was that it encompassed not just the usual suspects in anarchist and left-wing social movements and political parties, but also high school and university students, as well as many immigrant and precarious workers. In addition to responding to the difficult and deteriorating situation facing them as a result of decades of neoliberal policies, the groups participating in the uprising were also reacting to the first wave of bank bailouts in Greece, as well as to the proverbial corruption of the Greek political class.

By weakening the conservative government at the time, the December, 2008 revolt helped to pave the road to the "socialist" party’s victory in the fall of 2009. The "socialists" ran on an anti-austerity platform but quickly reversed themselves, instituting a brutal austerity program in exchange for loans from the European Union, the IMF, and the European Central Bank. These loans allowed Greece to continue servicing its debt and unsuccessfully sought to prevent a generalized debt crisis across the continent.

The austerity program inaugurated in May 2010 has effected a brutal assault on salaries and wages in the public and private sector, instituted successive cuts of pensions, liquidated labor and collective bargaining rights, instituted social security reforms that will force people to work many more years before they can retire, and dramatically cut the rudimentary welfare state that Greece had built up to this point. Not surprisingly, this program has produced a deep economic depression, with the Greek economy expected to shrink by at least 25 percent over the program’s duration, while official unemployment rates have skyrocketed to over 25 percent, with youth unemployment standing at around 55 percent. As a result, Greece now has the dubious honor of leading Europe in unemployment, having recently surpassed even Spain, the country that had for years experienced the highest unemployment rates in the continent.

Meanwhile, poverty has risen rapidly and so have hunger and despair, as illustrated by a rapid growth in the number of suicides. While many of the suicides have been the product of desperation, others have been carried out in protest to the social barbarism that the austerity program has produced. For example, in a case covered by media around the world, a retired pharmacist shot himself in front of the parliament a few months ago, leaving behind a note lambasting the Greek political elite for surrendering national sovereignty and obediently implementing the extreme austerity program dictated by Germany.

Protest has of course expressed itself in other forms as well. Strikes are a daily occurrence, as every sector of the Greek working class is under brutal assault, while there have also been over twenty general strikes in the last three years. These strikes are usually accompanied by militant demonstrations that often lead to brutal repression by the police, who beat protesters as well as journalists, while also making liberal use of tear gas and stun grenades.

Occupation of public space and squares has been another tactic used by the protesters, a tactic which had also been widely used during the December, 2008 revolt and which has been central to the repertoire of collective action of the Greek student movement for decades. The use of this tactic to protest austerity reached a peak in the summer of 2011, as Syntagma square, located in the middle of Athens and across from the Greek Paliament, was occupied for weeks. In part inspired by the Indignados in Spain and, before them, the example of Tahrir Square, this movement also prefigured the eruption of the Occupy movement in the United States and around the world. In line with the Greek government’s repressive approach to protest, the occupation ended as a result of police intervention in July, 2011. Moreover, university asylum was recently revoked to make it more difficult for the student and popular movements to use occupied universities as a site of resistance to the austerity onslaught.

Although the movement has not yet been successful in reversing the austerity program, it has produced a political earthquake by delegitimizing the conservative and "socialist" parties that had for decades dominated the political landscape in Greece. This earthquake has been the product of the failure of the pro-austerity camp and the troika, made up of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, to make good on the promises that were originally made regarding the austerity program’s likely results.

As the International Monetary Fund recently admitted, the assumptions underlying the austerity programs in Greece and the European South greatly underestimated the contractionary effects of austerity policies. The result has been a death spiral for the Greek economy that has increased the burden of debt as percentage of GDP. Thus, the first loan agreed in May, 2010 did not allow Greece to regain the confidence of global financial markets. Hence, a second loan and a restructuring of Greece’s privately held debt became necessary in early 2012. Also accompanied by harsh austerity measures, this second loan was supposed to allow Greece to reduce its debt to 120 percent of GDP by 2020, a level comparable to the level that triggered the debt crisis back in 2010. By the time I write these lines in October, 2012, it is clear that even this goal is not likely to be achieved. This has created tension between the IMF and Greece’s European creditors, as the IMF has come to recognize that Greece’s debt will not be stabilized by the present policies and that a further restructuring of Greece’s publicly held debt is necessary. This prospect is not appealing to European politicians who feel that their electorates would not welcome any more financial support for Greece.

As for Greeks, they have lost patience for austerity policies that do not seem to lead anywhere. While some Greeks were originally willing to give the then new socialist government the benefit of the doubt when austerity policies were first introduced in 2010, by now they have abandoned the socialist party in droves. In fact, the socialist government elected in 2009 had reached its limits by fall, 2011 and the continuation of austerity after that point was made possible only through the unprecedented formation of a coalition between the socialists, the conservatives and a racist, anti-immigrant party of the extreme right.

This coalition lasted until May, 2012, when elections were held. Support for the pro-austerity parties collapsed, while anti-austerity parties of the left and the right saw their support grow significantly. Especially impressive was the rise of the Coalition of Radical Left (Syriza) from the status of a minor political party with 5 percent of the electorate to a contender for power as its support grew to 17 percent in May and 27 percent in the June election that followed after the May election proved inconclusive.

While the rise of Syriza is a hopeful development, the also meteoric rise of neo-Nazi Golden Dawn is very disturbing. Adopting a racist and xenophobic message, Golden Dawn has not only capitalized on people’s anger and insecurity by looking for scapegoats on whom to blame the crisis and its devastating effects. Its members routinely attack immigrants, while trying to pose as a philanthropic force through programs that distribute food and services only to Greeks.

The Golden Dawn phenomenon is arguably not unique to Greece, as the impressive performance of the far right in France’s election last spring shows. This rise of the fascist and racist far right serves as a reminder that one of the main challenges facing the left around the world today is to prevent a reactionary response to the crisis by making clear that it is not immigrants who are to blame for this crisis but the capitalist system itself.

We are entering a period of intensifying social and class conflict globally, so it is urgent that the left rise to the occasion. Greece exemplifies the attempt of capitalist elites to impose on us a dark future without giving us a say on the matter. Ordinary Greeks are fighting back, however, so the game is not over yet. The rise of a left that is by now leading in the polls raises the possibility that an alternative strategy of dealing with the current crisis may soon be put to the test. Given the rapidly deteriorating situation in Greece, such a left government would be faced with huge challenges. It is also presented with the opportunity to act as a catalyst for changes throughout the European continent and beyond. As progressive forces around the world are grasping for alternatives to the current strategy of "solving" the crisis on the backs of those least responsible for it, they can be expected to learn from Greece both about the high stakes of the struggle over austerity and about the opportunities for progressive (or even radical) change that capitalism’s current crisis presents us with.

Leave a Reply