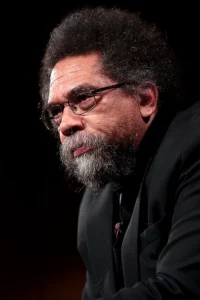

This is the ninth of a series of articles about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, but the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candidates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

This is the ninth of a series of articles about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, but the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candidates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

- George Edwin Tayler, candidate of the National Negro Liberty Party, sometimes known as the National Liberty Party in 1904;

- Clifton Berry, of the Socialist Workers Party in 1964;

- Charlene Mitchell of the Communist Party in 1968;

- Eldridge Cleaver with the Peace & Freedom Party in 1968;

- Dick Gregory as a write-in candidate in 1968;

- Channing Emery Phillips as a Democrat, all in 1968.

- Shirley Chisholm, Democrat, in 1972;

- Angela Davis, Communist Party for vice-president in 1984 and 1988;

- Jesse Jackson, Democrat, for president in 1984 and 1988;

- Ron Daniels, People’s Party candidate in 1992;

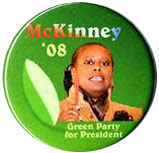

- Cynthia McKinney, Green Party candidate 2008;

- Barack Obama, Democratic candidate in 2008 and 2012;

- Cornel West, independent, in 2024;

- and finally Kamala Harris for vice president in 2020 for president in 2024.

We are currently (first week of August) editing these pieces. The essay on George Edwin Taylor has yet to be posted.

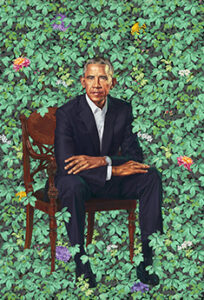

Barack Obama for President – 2008 and 2012

With Kamala Harris now running for president, it seems particularly pertinent to look at the career of first Black president to whom she is often compared.

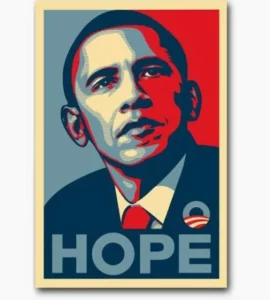

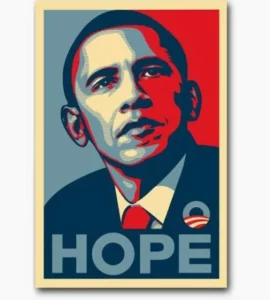

Today, fifteen years since he ran for president, it’s hard to remember that Obama was a candidate on the left. Not a leftist, of course, not even a radical, but he was perceived as a progressive. Elected on slogans of a vaguely inspiring character— “Hope” and “Change”—by voters who believed that he would end the Great Recession of 2008, withdraw the United States from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, do something to help the labor unions, deal fairly with the immigrants, and confront the environmental crisis. Eight years later it was clear that he either could not or would not do those things because he was fundamentally a centrist, corporate Democrat whose first allegiance was to high finance and big business. Obama was, despite his middle-class origins and unique multicultural upbringing, first and foremost a man of the Establishment. Given that he was the first Black candidate that won, we give here an extended account of Obama and his presidency.

In The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama, David Remnick writes that when he ran for president “…what Barack proposed as the core of his candidacy was a self—a complex, cautious, intelligent, shrewd, young African American man.”[1] The self that Obama offered to the American people was the product of a father born in Kenya and a mother born in Kansas, as he says, “he was black as pitch, my mother white as milk.”[2] The persona presented to America was the result of a childhood spent in Indonesia and an adolescence spent in Hawaii, a young adulthood spent in some of America’s finest colleges and universities, a few years in Chicago’s Black communities and churches, and finally a very short and surprisingly successful political career. Obama’s complicated family and upbringing gave him the ability to adapt to various situations, to assess and evaluate diverse social possibilities, and to speak eloquently in a variety of styles. He could be alternately a Black American, a cosmopolitan citizen of the world, and spokesman for a possible post-racial national future. His unique biography, his elite education, and his political instinct would elevate him into the Establishment and propel him to its heights.

The Making of Barack Obama

Barack Obama’s mother Ann Dunham, a white woman from Kansas, met his father Barack Hussein Obama Sr., a Black man from Kenya, in a Russian language class at the University of Hawaii in 1960. They could not have been more different. Dunham’s family were Protestants in Republican Kansas, her father was a furniture salesman and her mother worked in pink collar jobs, eventually becoming a bank executive. Obama, Sr.’s Kenyan father had worked as a cook for a wealthy Briton, was a modest farmer, herbalist, and healer. Raised in the Unitarian church, Dunham became an atheist, while Obama, Sr. was a non-practicing Muslim. The young, liberal, idealistic Dunham, a product of the early 1960s, fell in love with Obama, Sr., a protégé of a left nationalist politician in Kenya. He kept secret from her the fact that he already had a wife, a child, and another baby on the way back home in Kenya. The two married in February of 1961 and Barack Hussein Obama, Jr. was born in August. Shortly thereafter Obama, Sr. went off to study at Harvard, abandoning his new wife and child.[3]

Two years later, still at the University of Hawaii, Dunham, now a student of anthropology, met and became enamored of Lolo Soetoro, and in 1967 set off with her son Barack to live with Soetoro in Jakarta, Indonesia. The young Barack Obama studied from the age of six to ten at St. Francis, a Catholic, Indonesian language school, while his father rose in the ranks of the American Union Oil Company and his mother studied village life and crafts. At about the time that Ann Dunham had a second child, Maya, the parents began to grow apart. Now with two divorces and a single mother, Dunham, concerned about the young Barack’s future, took him to Hawaii where he lived with his grandparents and with a good word from a family friend and a scholarship, was accepted at the finest private school on the islands, Punahou, a school comparable to Eastern Establishment schools such as Exeter.[4]

If Hawaii wasn’t the one true racial melting pot that people thought it was, it was more diverse. than most of the United States, with Hawaiians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, Puerto Ricans making up about two-thirds of the population, it was less racist than many states in the union—though it had virtually no Black population.[5] Growing up in Hawaii as an adolescent in the 1970s, Obama was completely cut off from the experience of Black life and of the civil rights and Black Power movements on mainland America. But, while living in Honolulu and going to high school, Barack’s father introduced him to an older Black man named Frank Marshall Davis.[6] A former journalist with Black newspapers, a poet, and pornographer, Davis had probably been a member and was certainly a fellow traveler of the Communist Party active in several of the literary and activist party front groups on Chicago’s Southside in the 1930s.[7] Davis became Obama’s friend, a mentor who could teach Obama about Black life and about the old left as well. Perhaps it was Davis who stirred Obama’s interest later in becoming an organizer in Chicago.

Obama’s studies at the Punahou prep school, amidst its ethnically diverse student body, opened the doors to an elite higher education. With mediocre “B” grades Obama could not get into the Ivy League schools at first, as some of his classmates did, but being from Punahou he had his choice of private liberal arts colleges. He chose to go to Occidental College in Los Angeles, another school with a rather diverse student body but with few Black Americans. Like other students, but no doubt more so, he wrestled with his identity, experimented with alcohol and drugs, and briefly flirted with activist politics. Socialists and activists in other groups on Occidental’s campus joined together to organize a rally to push the college trustees to end investments in South African businesses. Obama spoke at the rally, perhaps his only moment as a college campus activist.[8]

Obama made the important decision in 1981 to transfer from Occidental to Columbia, in New York City, one of the Ivy League colleges. There he was a serious student, though he also took an interest for a short while in the nuclear-freeze movement. After graduating from Columbia in 1983, he worked for a year for Business International Corporation, a business and financial consulting firm, doing economic research; he was bored by the work but was paying off his debts. The following year he went to work for the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), a reform organization founded by attorney Ralph Nader. For NYPIRG Obama organized college students to support a campaign to improve public transportation, a job he enjoyed and excelled at. But, having become inspired by the history of the civil rights movement, Obama wanted to become a community organizer.

So Obama moved to Chicago where Saul Alinsky had established community organizing as both a form of organizing working class neighborhoods and as a profession. Obama began work for a Catholic Church-based group on the Southside of Chicago, one of the country’s largest and most important black communities. Community organizations, usually funded by corporate foundations, directed by liberals, and staffed by earnest college-educated young people engaged in organizing for the most modest sorts of reforms, and often with little success. (I myself was a community organizer in Chicago during the same period and am all too familiar with the fundamentally liberal and ineffective nature of such work.[9])

While Obama lived in Hyde Park, the mostly white neighborhood around the University of Chicago, for the first time in his life he spent all day, virtually every day on the Southside with Black people, mostly working class or simply poor. Obama’s work, while it had a minimal impact on their lives, nevertheless provided him with a new Black identity. He joined the Trinity Church of Rev. Jeremiah Wright, the politically involved and progressive black preacher, becoming a Christian, a Protestant. The church would later be an important base of his activity, but it’s preacher’s radical prophetic pronouncements proved an embarrassment. He observed firsthand and critically the administration of Mayor Harold Washington, who had in 1983 become Chicago’s first Black mayor. And, after breaking up with a white girlfriend, Obama met and began to keep company with Michelle Robinson. After his experience in Chicago, he decided to pursue a career in politics, so in 1988 he left Chicago for the Harvard University Law School.

Harvard was the front door of the Establishment, and in walked Barack Obama. As his biographer Remnick writes, “At Harvard, he would join the world of the super-meritocrats of his generation, shifting from outsider to insider.”[10] With the law school more or less socially self-segregated—Blacks and whites eating separately—and bitterly divided between radicals, liberals, and conservatives, Obama always attempted to rise above the controversy and find consensus.[11] While he spoke at a public rally in support of a Black woman professor who was being denied tenure, everyone remembers Obama as being non-ideological and always a seeker of reconciliation. Obama joined the Black Law Students Association, and studied with professors, white and Black, who held a variety of political views, but he chose as his intellectual mentor Lawrence Tribe, a liberal professor for whom he became a researcher. Obama also joined the staff of the Harvard Law Review, the “inner sanctum of the establishment,” and was elected its first Black president, an event important enough to be reported in The New York Times.[12]

Roberto Mangabeira Unger, one of his professors who was a Brazilian socialist who later served in the government of Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, wrote that at Harvard Obama achieved a style of “cheerful impersonal friendliness,” which Unger called, “the style of sociability most prized in the American professional and business class.” Unger goes on: “Together with the meritocratic educational achievements, the mastery of the preferred social style [turned] Obama into what is, in a real sense, the first American élite President—that is the first who talks and acts as a member of the American élite—since John F. Kennedy.”[13] With his law school record, Obama could have any job in the legal profession that he wanted.

Starting Life Over in Chicago

Obama moved back to Chicago where he took a job with the best-known civil rights law firm and became a lecturer in law at the University of Chicago Law School, moved in with and soon married his girlfriend, Michelle. He began to write his brilliant and politically important autobiographical book Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. In 1992, a Democratic Party lawyer hired Obama to head Project Vote, aimed at registering the hundreds of thousands of unregistered Blacks in Chicago with the goal of electing Bill Clinton to the U.S. presidency. Funded by Black and white businesses, Project Vote contracted a Black public relations company, and hired eleven thousand registrars. Obama trained 700 of them himself. Using his contacts from his community organizing experience Obama was tremendously successful, contributing to the election of Bill Clinton and other Democrats, and giving Obama important contacts among Black leaders and also among the wealthy Lakefront liberals “who would help form the financial base of Obama’s political campaigns.”[14]

In 1997 Barack Obama entered his first political campaign, running for the Illinois State Senate. The most interesting thing about Obama’s entrance into electoral politics was the qualmless way in which he did it. Despite his brushing acquaintance with campus radicalism at Occidental and Columbia and his studies with some left wing Critical Legal Studies professors at Harvard, Obama completely, absolutely, and uncritically accepted the political system just as it was. His first campaign was largely financed by wealthy business people, organized through the Democratic Party’s formal structure, and largely carried out in the traditional manner with the usual door knocking, phone banks, public speeches, and campaign literature.[15] His campaign was not distinguished by a progressive program. There was nothing progressive, much less radical, about it. True he worked with the Lakefront liberal Democrats rather than the Chicago machine, but neither in form nor content did Obama question much less challenge the usual American relationship between corporate interests, the party, and the government. A skillful networker with a good organization he won 88 percent of the vote and became an Illinois State Senator.

The Illinois legislature, dominated by Republicans, frustrated and bored Obama. Throughout his years there from 1997 to 2004, his main concern was to establish a political career and to avoid controversy, so like many other legislators, he often voted “present” rather than “yes” or “no” on hot-button issues such as abortion. In fact, he did so 129 times, more than many others, giving him a reputation for spinelessness.[16] In his last couple of years in the state senate, however, he worked with party leaders to establish a left-of-center legislative record. Anxious to move ahead in his career, in 1999 Obama decided to challenge the incumbent U.S. Congressman, former Black Panther Bobby Rush, a man seen by his predominantly Black district as a hero of the civil rights and black power era. While Obama had adequate financing and organization, he was crushed in the 2000 election by Rush who won 60 percent of the vote to Obama’s 30, other votes going to minor candidates. Black voters felt that Obama was “not Black enough,” that he was elite, effete, and aloof to the point of arrogance.[17]

The one important political stance that Obama took in this period occurred following the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon as George W. Bush was preparing to lead the United States into war against Iraq. Obama spoke at an anti-war rally in Chicago in September 2002 supporting Bush’s call “to hunt down and root out” the terrorists, but opposed the call for war against Iraq. “What I am opposed to is a dumb war. A rash war. A war based on passion, not on principle, but on politics.”[18] While Obama was not an outspoken or consistent opponent of the war, that speech would establish his underserved reputation as a peace candidate, a key to his future elections as senator and president.

Obama used his defeat by Black Panther Rush to redefine himself both racially and politically. Using the Biblical references of the Black church, Obama would refer to the famous civil rights leaders—Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesse Jackson, and others—as the “Moses generation,” a generation of leaders of protest, and to himself as part of the “Joshua generation,” a cohort of modern, non-ideological, young Black men and women who believed in negotiation, compromise, and reconciliation. Being in Chicago, home of the veteran civil rights leader, Rev. Jesse Jackson, twice candidate for president and omnipresent protestor whose angry words often alienated and frightened whites, Obama had to establish his identity vis-à-vis him. As David Remnick writes, “Obama’s manner, his accent, his pedigree, his approach to the issues, told white voters, among other things: I am not Jesse Jackson.” At the same time, Obama, “relentlessly channeled the legendary life and outsize oratory of Martin Luther King, Jr.” [19], even as he was moving away from that model of Black leadership. Most important, Obama developed his “signature appeal, the use of the details of his own life as a reflection of a kind of multicultural ideal, a conceit both sentimental and effective.”[20]

In 2004 Barack Obama, his carefully crafted political persona now completed and perfected, entered the race for the U.S. Senate. For this campaign he now had Chicago’s really big money, the Crown family, owners of the Hilton Hotels, Rockefeller Center, the Chicago Bulls, and the Pritzker family, proprietor, among many other things, of the Hyatt Hotels and the Caribbean Cruise Line. With a big treasure chest, Obama put together a large and highly professional team to capitalize on his base in the Black and liberal communities and to extend it to more conservative suburban and downstate areas. Obama’s big break came when, still just a candidate for national office, he was invited to give the keynote speech at the Democratic Party National Convention where John Kerry was being nominated for President.

Obama’s speech delivered in his “professorial and pastoral,” and yet passionate style electrified the audience both in the convention center and watching on television across the nation. People Black and white thrilled to the speech’s most famous lines.

Now even as we speak, there are those who are preparing to divide us…Well, I say to them tonight, there is not a liberal America and a conservative America; there is a United States of America. There is not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there is the United States of America.

He concluded by asking, “Do we participate in a politics of cynicism, or do we participate in a politics of hope?” Obama won the 2004 senate election with a spectacular 70 percent to the Republican candidate’s 30 percent.[21] Though he had just been elected to the Senate solely because of the impact of his keynote speech, and has just taken office, all that the reporters and the public wanted to know was, “Will you run for president?”

As a brand-new U.S. Senator, ninety-ninth out of one hundred in seniority, Barack Obama had little influence, but in any case, he kept his head down. He voted with the Democratic Party on virtually every issue, establishing one of the most liberal voting records in the Congress.[22] Yet, as two New York Times reporters wrote, “He was cautious — even on the Iraq war, which he had opposed as a Senate candidate. Though he spoke in favor of a drawdown, he voted against the withdrawal of troops.”[23] The one issue where he played a prominent role was an ethics bill.

Being Senator provided him an opportunity to establish his foreign policy credentials. He went with a bipartisan delegation to Ukraine, Russia, and Azerbaijan to inspect weapons storage facilities. Another political trip to Africa, with a stop in Kenya where he spent time with his grandmother, which led to by media around the world. As biographer David Remnick writes, “The extraordinary reception Obama received seemed to demonstrate the effect he could have in altering the battered image of America that had taken hold all over the word during the Bush Administration.”[24]

With the Bush administration in crisis internationally with the continuing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and domestically with the terrible mishandling of Hurricane Katrina—where 1,392 people had died in New Orleans—and with the beginnings of a recession, the Democrats had a good chance of winning the 2008 presidential election. Obama entered the race for the Democratic Party nomination for president in 2007, running against former First Lady and Senator Hillary Clinton. The election of either a woman or a Black American would be historic. Bill and Hillary Clinton had the most powerful political fundraising operation and many experienced political operatives, but in a closely fought contest, Barack Obama put together a nearly equally formidable operation. One of the most interesting and telling moments of the campaign came when in an unguarded moment, Obama, speaking to Californians about blue collar voters old factory towns in Pennsylvania, said, “They get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.”[25] Clinton seized on the remark to condemn Obama’s “elitism,” and, while there was much truth in Obama’s remark, it also suggested the degree to which Obama and the Democratic Party had lost touch with the working class.

In the end, Obama defeated Clinton winning the Democratic Party nomination. He had raised more corporate money and more money through individual contributions that any previous candidate. Shepard Fairey’s striking poster with a stylized portrait of Obama and the word “HOPE ” caught the public imagination. Hope and change became the watchwords. Obama’s presidential campaign took on the character of a social movement, enthused young people, and inspired the nation. At the same time Republican candidate John McCain chose the rightwing populist Sarah Palin as his running mate and the two ran a down-and-dirty, red-baiting and race-baiting campaign. Obama won 53% of the popular vote to McCain’s 46%, and won the Electoral College vote 365 to 173. The Democrats also won both houses of Congress, putting Obama in a position to push his agenda and change the direction of the country.

Obama worked to create the impression that he was not only a Democrat, but also a progressive and even the candidate of the left. What did the voters who elected Obama expect of him? First, having heard his anti-war speech, they expected him to end the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. With his liberal reputation, they expected him to help labor unions and working people, to find a solution to the immigration issue, and to face the looming challenge of environmental catastrophe. As a Black man, naturally they expected him to be better on issues of race and policing. But most importantly, at the moment he took office they wanted him to deal with the failure of the country’s financial institutions and the crash of the economy that had taken place just as he was elected. Tens of thousands of people were losing their jobs while some were losing their homes and they wanted the government to do something. Bush had signed a $170 billion stimulus package and the government had taken over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored mortgage guarantee programs, but just before the election Lehman Brothers, one of the country’s largest financial companies, had filed for bankruptcy and other banks were on the verge of collapse.

Obama and the Great Recession

When Obama took office as president, the economic crisis was still unfolding, but it was clear from early on that many banks had engaged in dubious and perhaps illegal practices in the handling of mortgage securities. Speculation in bundled, securitized, subprime mortgages led to bursting bubbles in 2007 and 2008 and to the folding of a slew of mortgage lenders—more than a hundred of them—and then to the collapse or near collapse of several major banks and other financials including AIG, Bear Stearns, Citigroup, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, IndyMac, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Wachovia, and Washington Mutual. The U.S. government—first under George W. Bush—intervened to arrange mergers, to take over banks temporarily, and to pump hundreds of billions of dollars into the financial sector, nevertheless, the financial crisis ramified through the economy sweeping away $19.2 trillion in household wealth as banks foreclosed on 12.5 million homes between 2007 and 2013.[26] The 2008 depression eventually wiped out more than two million jobs in the first year, affecting virtually every sector of the economy from mining to manufacturing to services and soon leading to an official unemployment rate of 10 percent, though many thought the real jobless rate might well be 16 percent.[27] Millions of Americans found themselves without work, some without homes, and many without prospects as the recession dragged on.

Obama meets with bankers. White House photo. Obama told them, “My administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks.”

What would Obama do? A new president with a majority in Congress and with much support among the public could have used his power to do just about anything that he pleased with the banks and the bankers—short of nationalizing them, which in America would have been unprecedented and have required a major political battle. He could have placed himself firmly on the side of the people against the banks. He had, however, already dumped his more progressive advisors, Karen Kornbluh and Austan Goolsbee, and replaced them with Wall Street bankers.[28] Obama’s elite education and training prepared him, however, to see the financial crisis as a crisis of his class, the class of which he had become a part, the capitalist ruling class. He felt himself one with the political and economic Establishment, and moved to protect the common interests of the powerful and wealthy.

So, he moved methodically to back the bankers. Following the suggestions of his advisor Michael Froman of Citigroup, Obama chose central banker Timothy Geithner, an associate of the Rubin school of Goldman Sachs and Citigroup bankers, to be his Secretary of the Treasury. As David Dayen wrote in The New Republic, “The Rubin school dictated the Obama administration’s light-touch policy on bank misconduct…”[29] Meeting with thirteen CEOs of the country’s largest banks, Obama told them, “My administration is the only thing between you and the pitchforks.”[30] Obama proved to the bankers that he prepared to stand between the bankers and the angry public and ambitious public prosecutors.

Obama told the bankers, “Help me help you.”[31] And they did. With Obama’s aid the U.S. government put up the money to save the banks, but there were no serious legal or fiduciary consequences for any of the bankers. No bankers were prosecuted for their roles in the dubious, immoral, and in some cases illegal financial operations they had conducted. No banker went to jail. The U.S. government put up $700 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, which both bailed out the banks and provided aid, though all too little, to homeowners facing foreclosure. And at least $150 billion went to save Fannie Mae and Fredie Mac. So, the banks were saved, while across the country demonstrators who had lost their homes chanted, “Banks got bailed out, we got sold out.”

Automakers were also failing and Obama moved quickly to save General Motors and Chrysler, though in that case he pressured the head of GM to resign. Obama’s salvation of the auto industry, much like Democratic President Jimmy Carter’s Chrysler bailout of 1979, came at the expense of workers’ jobs, benefits, and wages. Under Obama’s plan, which loaned $80.7 billion to the companies, the carmakers closed several dozen plants, made health insurance more expensive, and established lower wages for new workers, while also closing many dealerships.[32] Thousands of auto workers and dealership employees lost their jobs, and new hires in the auto plants came in at wages sometimes half those of their predecessors. With the government’s help and the United Auto Workers cooperation the industry’s corporations were saved, though for unions and workers the bailout was a tremendous defeat. The UAW ceased to bear any semblance to the militant, social democratic union it had once been, while many union members now made little more than non-union workers.

Some believed and others hoped that Obama would be another Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Democratic Party president who during the Great Depression of the 1930s established public works programs that put hundreds of thousands of people to work. More liker Herbert Hoover than FDR, Obama saw his job as restoring the functioning of the economy and returning the corporations to profitability.[33] Obama’s stimulus program was estimated at a total of 2.8 trillion dollars, but about 40 percent of that was in the form of tax cuts that principally benefitted individuals and businesses.[34] Most of the rest, usually estimated at $800 billion, we have already accounted for was in the form of loans to the banks and the auto companies.

Nobel prizewinner Paul Krugman, a liberal, Keynesian economist, pointed out that FDR himself had failed to have much impact on unemployment during the Great Depression because he was not sufficiently bold.[35] Obama was far less bold. Beginning in January 2009 and for several years afterward, Krugman criticized Obama regularly in his New York Times column “The Conscience of a Liberal” for the inadequacy of his stimulus plan and its failure to help reduce unemployment significantly. Five years after the beginning of the Great Recession, 57% of Americans believed the United States was still in recession. At that point it was estimated that the economy still needed seven million jobs to recover from the recession.[36] Six years later one study found that 93% of U.S. counties had not fully recovered.[37] Barack Obama, the liberal, and the Democratic Party, the party of working people, were in power, and yet working people could see that their lives were deteriorating and their government wasn’t doing enough to help. Many would leave to join the Republicans and later support Donald J. Trump.

President Barack Obama, official portrait.

Obama’s Domestic Policy

While the economic crisis preoccupied Obama for his first several months in office, he also had to deal with the issues that concerned so many of his constituents: education, labor laws, immigrant rights, and the environment among others. Many Americans felt that the public schools were not meeting the students’ needs: too many students failed to achieve at grade level and many Black and Latino students dropped out of school before graduation. During the administration of Bill Clinton, Republicans and Democrats had joined together to create the “common core standards,” establishing basic standards for students’ knowledge of English and math. George W. Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” program, passed with bipartisan support, promoted “standards-based education,” which led to “teaching to the test,” rather than teaching to the student. Many urban schools concentrated on training students to pass tests, while eliminating physical education, music, and arts programs. Teachers and their unions rejected that approach and argued for more funding for education and for smaller class sizes.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the official name for Obama’s stimulus program, included an education program called “Race to the Top.” Secretary of Education Arnie Duncan oversaw and implemented the program. The heart of “Race to the Top” was the carrying out of performance-based evaluations for principals and teachers, relying on students’ test scores on the common core curriculum with records kept in a national database. All of this was reported in the biennial National Assessment of Educational Progress, a report card on reading and math. When schools didn’t improve within five years, they were closed, and thousands of teachers were fired along the way. At the same time Duncan encourage the expansion of private charter schools. Teachers’ unions and many parents hated the “Race to the Top,” which also proved ineffective in improving children’s schooling. In fact, though Duncan’s Department of Education spent $4.3 billion, there was no evidence that “Race to the Top” had done anything to improve students’ education.[38]

Obama’s principal presidential achievement, the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare as it came to be called, was signed into law in March of 2010, Republicans hated the plan because it taxed people with higher incomes to subsidize health care for those with low and middle incomes, carrying out a modest redistribution of wealth that also in a very small way acted to reduce income inequality. But it was not the “socialist” program that the conservatives claimed. A socialist program would have provided free, full medical coverage to the entire society financed by taxing corporations and the wealthy. Ironically, Obama’s plan was first proposed by the conservative Heritage Foundation.[39] The Obamacare law was written by the insurance, health care, and pharmaceutical industries,[40] and it didn’t create universal coverage, as many had hoped, but forced Americans to buy private insurance that was often too expensive. Nothing like the universal coverage in most European countries, this remained a capitalist market insurance system with caps on certain payments, co-pays, and select pools of doctors.

True, Obamacare extended and improved insurance coverage for 20 million Americans and made health insurance more comprehensive. But, while nine million previously uninsured people did get health insurance, some 33 million—about ten percent of the population—were still left without it. The health care system remained “complex and confusing” and health care continued to become more expensive, too expensive for many. As the New York Times wrote at the time, “The health insurers are the most direct beneficiaries of the law.”[41] A columnist for Forbes wrote an article the title of which told all: “Obama care enriches only the health insurance giants and their shareholders.” He stated there that, “the ramification of ObamaCare…was to multiply the profits of five giant insurance companies.”[42] Over the following years, the number of uninsured fell dramatically, yet last year, 25.6 million people, 7.7% of the population had no health care insurance.

Immigration was also on Obama’s agenda. President George W. Bush in 2004 pushed Congress to pass a comprehensive immigration reform, but failed, largely because of conservative opposition in his own Republican Party. Obama had promised immigration reform during the first year of his first term, but hopes for some sort of comprehensive immigration reform also soon evaporated.[43] Obama, claiming he was too busy dealing with the economic crisis in his first two years delayed his major legislative proposal until 2013, after he had lost his congressional majority in both houses.[44] The Republicans also blocked his plan. With massive immigration from Mexico continuing during his first six years in office, Obama turned to deportation to deal with the issue, winning the unofficial title of “deporter-in-chief.” Under Obama, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported more than 2.5 million people between 2009 and 2015, more than his predecessor Bush.[45]

Labor law reform had been on the Democratic Party agenda since the days of President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981). The idea that unions might win a law permitting card-check elections, where a simple majority of workers signing cards could establish a union, or some other sort of labor law reform also disappeared. Such a change was only possible during the first two years of Obama’s administration when the Democrats had a majority in Congress, but on the labor reform issue, as on so many others, Obama failed to strike while the iron was hot. Republicans, now with a majority, took advantage of their ability to paralyze the U.S. Congress then went on the offensive in the states, rolling back the unions’ gains of earlier years, in several states eliminating the agency shop among public employees, where all workers must either join the union or pay a fee, and ending the union shop in the private sector in a few. Republicans pushed for “right-to-work” laws, that is, the right to work for a government agency or private company without joining the union. West Virginia passed a right-to-work law in 2016, the twenty-sixth state to do so, joining Midwestern states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana where such laws were unthinkable only a few years before.[46] With Obama in power, the American labor unions not only continued to decline but also experienced a qualitative loss of economic and political power. Union membership fell to 10.7 percent, but only 6.4 percent in the private sector, the lowest in American history since the 1920s.

On the question of the environment—which virtually all scientists believed was now in danger of catastrophic change because of greenhouse gasses—Obama made minimal reforms while failing to provide leadership to confront the looming planetary disaster. According to one report based on interviews with leading environmentalists, Obama was given credit for “setting strict vehicle mileage standards and funding energy efficiency and renewable energy projects.” But, “Most [environmentalists] felt the president’s greatest failures were his tepid support of climate legislation, which ultimately went down to defeat, and his refusal to rally the country to fight global warming.”[47] In the YaleEnvironment360 forum on Obama’s energy policy, Joseph Romm of Climate Progress made the harshest critique, writing that, while he principally blamed “the anti-science, pro-pollution ideologues” for the failure.

Obama’s overall record on energy and the environment deserves an F. Fundamentally he let die our best chance to preserve a livable climate and restore U.S. leadership in clean energy — without a serious fight. Future generations are thus still headed toward a world of 10 degrees F warming, widespread Dust-Bowl-ification, ever-worsening extreme weather, seas several feet higher and rising several inches a decade, and a hot, acidified ocean filled with ever-worsening dead zones.[48]

In the big picture, Obama’s vehicle mileage standards meant little. He failed his constituents, the country, and the planet.

Obama’s election as the first Black president was a source of enormous pride for the African American community—he won 96 percent of the Black vote in both elections and generally has an approval rating of 80 percent among African Americans. Black people, of course, hoped that the first Black president would do something to better their lives, to improve their economic conditions, and to protect their rights. By and large, those hopes were not fulfilled. Black Americans were, however, loath to criticize the president, still, a number of Black leaders—members of the Congressional Black Caucus, civil rights leaders, religious figures, intellectuals and activists—courageously complained that Obama had failed the Black community in terms of both economic issues and racial justice.[49] In 2013, Benjamin Jealous, head of the NAACP, told Meet the Press that Black people were no better off under Obama, and in fact they were doing worse.[50] Tavis Smiley, the radio and TV talk show host, argued in 2014 that during Obama’s presidency Black’s had “lost ground.”[51] Prof. Cornel West, the most radical and outspoken of Obama’s Black critics told Salon, “He posed as a progressive and turned out to be counterfeit. We ended up with a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency.”[52] He was right.

Always more vulnerable than whites because they had far fewer economic assets to begin with, the Great Recession of 2008 stripped many Blacks of their homes and bank accounts because they had lost jobs and suffered foreclosures. Under Obama, the wealth gap between whites and Blacks not only persisted, it widened. In 2010, whites had eight times the median wealth of Blacks, but by 2013, whites had 13 times the median wealth of Blacks.[53] As William A. Darity, Jr., a Black scholar at Duke University explained in an article in The Atlantic, Blacks at every level of education had twice the unemployment rate of whites. Even when Blacks had some college education, they had higher unemployment rates than whites who never graduated from high school. Moreover, the relative economic position on virtually all indicators, including the racial unemployment rate gap, had not improved since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[54] Black Americans saw little improvement in their economic life under Obama. Darity blamed Obama for accepting the white racist argument that Black culture was responsible for low educational levels, low employment, and low incomes, and that it was up to Black individuals and families to change their behavior and lift themselves out of poverty, with some government economic assistance but with no real structural changes.

Darity argued that,

The Obama administration never gave serious consideration to aggressive transformative universal policies like a public-sector employment guarantee for all Americans, a federally financed trust fund for all newborn infants with amounts dictated by a child’s parents’ wealth position, or the provision of gifted-quality education for all children. These are universal programs that can have a significant “disproportionate impact and benefit for African Americans,” in the process of helping all Americans—unlike the types of universal programs endorsed by the president. And the emphasis on exclusively universal programs yields the spectacle of a black president who opposes the most dramatic black-specific program of all—reparations for African Americans.

Obama should not be blamed for creating Black’s economic problems—the roots of which lay in the Reconstruction of the 1860s and 70s and in the decades of Jim Crow—but he was to be faulted for failing to ameliorate their conditions and for blaming Black people for their problems.

Obama also failed to make advances in the area of Black rights. In Obama’s first term, George Zimmerman, a volunteer in a neighborhood watch program, had apparently stalked, assaulted, and assassinated a boy name Trayvon Martin—and was found innocent. In that case, much to his credit, Obama spoke out first saying that Trayvon could have been his son and later, “Trayvon Martin could have been me thirty-five years ago.” As Dyson writes, he “threw the enormous weight of his office behind the black teen from Florida.”

During Obama’s second term a series of police killings of unarmed black men—Eric Holder in New York, Michael Brown in Ferguson, and Freddie Gray in Baltimore—led to mass protests across the country and to a new organization, #BlackLives Matter. Obama’s response to those police killings was mixed. In the case of Garner in New York, Obama called for a task force to study how to strengthen relations between the police and communities of color.[55] In Ferguson, Obama sent Eric Holder to investigate and Obama’s ally Rev. Al Sharpton also went in to try to tamp down the protests.[56] And, in the case of Baltimore where there was a full-scale black uprising, Obama referred to the protestors as the “criminals and thugs who tore up the place.”[57] By and large, Obama did not speak out consistently against racist police violence as he might have and did not speak up for the protest movement, no doubt for fear of losing his support from the Establishment and from many whites.

Black scholar Michael Eric Dyson, sometimes a critic but mostly an apologist for Obama, wrote something interesting in his book Black Presidency. “If Obama’s delivery on race is sad and disappointing, the failure of most black Americans to hold him accountable is no less so.” One of the results of this, as Dyson points out, was that “…it guaranteed that black Americans would continue to get what they did not deserve: a president who was afraid to address their concerns effectively.”[58] Because Black Americans were proud of Obama and afraid of the Republicans, most feared speaking out, much less protesting, which for several years—at least until #BlackLivesMatter—condemned them to a lower standard of living and less protection of their rights.

Obama’s Foreign Policy

Obama was elected in large measure because the people of the United States were tired of the continuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, wars in which thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands of others had been killed.[59] Then too there was the financial cost: the Iraq War had cost $2 trillion,[60] while the Afghanistan War cost about $5 trillion.[61] And the damage to America’s reputation and image had been profound, while those wars also contributed to the continuing growth of terrorist networks throughout the region. In March of 2008, when he was still a candidate Obama promised, “When I am commander in chief, I will set a new goal on day one: I will end this war.” As president he vowed to defeat Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and suggested that he would end the Afghanistan war too. While Obama did reduce troop commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan, he failed to withdraw all U.S. troops, and he actually expanded military operations to several other countries. By the time he left office, the United States was involved in significant military operations in eight countries—Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, Cameroon, and Uganda, and the American government had troops deployed in some 82 nations.[62]

Not only did Obama continue the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and expand them in Africa, he also continued to maintain the U.S. role as the dominant military superpower. Obama and his Secretary of Defense, Leon Panetta, published a document, “Sustaining U.S. Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense,” in which Panetta wrote:

This country is at a strategic turning point after a decade of war and, therefore, we are shaping a Joint Force for the future that will be smaller and leaner, but will be agile, flexible, ready, and technologically advanced….It will have a global presence emphasizing the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East while still ensuring our ability to maintain our defense commitments to Europe, and strengthening alliance and partnerships across all regions.[63]

The most notorious example of this lean and agile approach was Obama’s use of drones, ostensibly to kill terrorists in Afghanistan or Pakistan, but often taking the lives of civilians.[64] While Obama carried out his “pivot toward Asia,” he also attempted to “reset” relations with Russia, to play the leading role in the Middle East during the Arab Spring of 2010, and to be the dominant power throughout the Americas. Nothing fundamentally changed in terms of foreign policy, except that Obama and his Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proved maladroit at times, particularly in the Middle East.

Besides the use of American military might, Obama continued to pursue the free trade policies of former presidents Bush and Clinton. His key trade program, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), was a bigger, broader version of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) of 1994 between Canada, Mexico and the United States, but this time with 11 other countries–Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. The proposed TPP, part of the pivot toward Asia, was meant to counter the growing economic power of China. As Public Citizen argued, “TPP will lead to more off-shoring, lower wages, and a weakening of environmental and health standards.”[65] TPP, like NAFTA and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TIPP), would also have given private corporations the power to sue national states before panels of corporate lawyers, thus violating national sovereignty and overriding democratically elected governments.[66] Obama’s TPP, which represented the program of the financial and corporate giants, not the interests of the working people of America, had little support among the population at large, yet the president continued to press for it until mid-2016, when it was clear that it would not pass Congress. President Donald J. Trump withdrew from it in 2017.

An account like this, simply running through the issues and explaining Obama’s position is not entirely fair to him. We have to remember that for the Republican Party, especially for the rightwing Tea Party movement and then the Tea Party caucus in Congress, and above all for the nativist base, Obama was the anti-Christ: a foreign-born Muslim, and somehow a socialist to boot. Obama faced a fierce racist attack from the Tea Party, some of whose members carried placards that depicted him as a gorilla or an African tribesman, that is, as a subhuman Black man. Michael Eric Dyson is probably right that, “Obama has faced levels of resistance that no president before him has confronted.” As Dyson points out, no other president faced so many death threats and no other had a representative in Congress shout, “You lie.”[67] The radical right grew and smaller Klan and Nazi groups proliferated. But one can argue that the far-right movements grew stronger in part because Obama failed to lead and build the liberal social movement that his 2008 campaign had nearly become. Obama’s constant attempts at conciliation and compromise with the right, repeatedly rebuffed, only helped to contribute to the decline of the Democratic Party and especially its left.

Democrats, especially white Democrats, who had placed so much hope in Barack Obama, hoping for the change that he had promised, began to desert the party. They had good reason to do so. As Robert B. Reich, former Secretary of Labor (1993-1997) in Bill Clinton’s administration, wrote in January of 2016:

Democrats abandoned the white working class.

Democrats have occupied the White House for sixteen of the last twenty-four years, and in that time scored some important victories for working families – the Affordable Care Act, an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Family and Medical Leave Act, for example.

But they’ve done nothing to change the vicious cycle of wealth and power that has rigged the economy for the benefit of those at the top, and undermined the working class. In some respects, Democrats have been complicit in it.

Both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama ardently pushed for free trade agreements, for example, without providing the millions of blue-collar workers who thereby lost their jobs any means of getting new ones that paid at least as well.

They also stood by as corporations hammered trade unions, the backbone of the white working class. Clinton and Obama failed to reform labor laws to impose meaningful penalties on companies that violated them, or enable workers to form unions with a simple up-or-down votes.[68]

The decline in working class support for the Democrats was remarkable. Between the economic crises of the 1970s and the age of War on Terror in the 2000s, many former union members and Democrats, independents, and Republicans moved into this world of conservative organizations and ideologies. So, it is not surprising that by 2015 it would be reported that, “Republicans hold a 49%-40% lead over the Democrats in leaned party identifications among whites. The GOP’s advantage widens to 21 points among white men who have not completed college (54%-33%) and among white Southerners (55%-34%).”[69]

Trump’s rise to the presidency cannot be understood without an appreciation of the role played by his predecessor Barack Obama. Obama’s presidency unintentionally contributed to Trump’s victory in several ways. First, the election of a Black man to the highest office in the country, galvanized the racist far right and conjured up the latent nativism and racism in a portion of the white population. Obama, remember, was accused by Donald Trump, other Republicans, and the conspiracy theorists known as the “birthers” of not being a U.S. citizen—as required by the U.S. Constitution in order to serve as president—but of being a citizen of either Kenya or Indonesia. Obama was also accused of being a Muslim, rather than a Christian, and perhaps associated with Muslim terrorists. In any case, Obama was made out to be a foreigner, unqualified for the presidency, and of dubious loyalty to America. The Tea Party demonstrations against Obamacare, with their signs depicting Obama as an ape, were in large measure racist rallies against the Black president. Much of the energy and animus of the Trump campaign came from the Tea Party’s earlier surge.

Second, beginning with his saving the banks and auto companies while neglecting the foreclosed and the unemployed, Obama proved to be a great disappointment to his followers. During his first two years in office Obama failed to take virtually any action on any of his platform planks and promises: labor law reform, and immigration reform, environmental legislation. He failed to end the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, an implicit promise of his campaign. By year three he had let the opportunity for change slip by. In developing what would be his principal achievement, the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, he refused to consider a single-payer option and working with health corporations, the pharmaceuticals, and insurance industries he created an expensive and complicated plan that still excluded 30 million or 10 percent of the population. And throughout his term, as he said, he declined to be “the president of Black Americans,” while supposedly acting as the president of all Americans. He ignored the economic decline of the Black population, often blaming Black people for their own misfortunes, and he failed to speak out consistently and forcefully against police racism and violence in the Black communities. Obama’s utter failure to carry out a progressive agenda laid the basis for the challenge to his presidency by Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders and later the successful bid by Trump.

Third, and finally, Obama made it clear throughout his presidency that—though he was Black—he was the representative of the overwhelmingly white American Establishment. Obama, though his administration discovered wrongdoing among some of the country’s largest and most powerful institutions, never prosecuted, convicted or jailed a banker. He put financial insider Timothy Geithner in the central position of Secretary of the Treasury. Obama retained in the key role of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, a hold-over from the George W. Bush administration. Many of Obama’s other cabinet appointments came from the dominant Democratic Party leadership, people like Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, both of whom served as Secretary of State. If he placed in positions of power Blacks like Eric Holder in the Attorney General’s office and Latinos like Hilda Solis as Secretary of Labor, they were people who posed no danger of challenging the fundamentals of the political and economic system. While the Democrats were better than the Republicans on many issues, from abortion to climate change, Obama’s record made it clear that his administration in no way represented any sort of progressive politics. His was the government of finance capital.

Obama hands over the office of president to Donald Trump, January 2017. VOA file. photo.

Many of those who had supported Obama, Black and white, were deeply disappointed. There was no change, and so from then on there was little hope for many. Obama’s victory demonstrates in every way the limitations of Black candidates who serve the Democratic Party, even when they come to lead it. The result was that millions of voters turned away from the Democratic Party to the Republicans, away from Obama and toward Donald Trump. A comparative study of various polls found that “estimates of the raw number of such Obama-Trump voters range from about 6.7 million to 9.2 million.” Trump won the presidency. That was the price we paid for Obama.

Notes

[1] David Remnick, The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama (New York: Vintage, 2011), pp. 3-4.

[2] Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (New York: Crown Publishers, 2004), p. 10

[3] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 29-40.

[4] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 41-70.

[5] Obama, Dreams from My Father, pp. 25-

[6] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 94-97.

[7] “Frank Marshall Davis,” Wikipedia, available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Marshall_Davis

[8] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 98-111.

[9] Dan La Botz and Thomas A. Dutton, “The Futures of Community Organizing: The Need for a New Political Imaginary,” Feb. 4, 2008, available at: http://arts.miamioh.edu/cce/papers/Future%20of%20Community.pdf

[10] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 182.

[11] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 187-89.

[12] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 207.

[13] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 186-87, quoting emails from Unger.

[14] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 224.

[15] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 271-293.

[16] Remnick, The Bridge p. 350.

[17] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 306-334.

[18] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 346-347.

[19] Michael Eric Dyson, The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2017), p. 71.

[20] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 360.

[21] Remnick, The Bridge, pp. 384-413.

[22] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 427.

[23] Kate Zernike and Jeff Zeleny, “Obama in Senate: Star Power, Minor Role,”

The New York Times, March 9, 2008, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/09/us/politics/09obama.html

[24] Remnick, The Bridge, p. 446.

[25] Ed Pilkington, “Obama angers midwest voters with guns and religion remark,” The Guardian, April 14, 2008, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/apr/14/barackobama.uselections2008

[26] “12.5 Million Homes Put In Foreclosure 2007-2012,” The Mortgage Daily Report, available at: https://themortgagereportdaily.wordpress.com/2013/09/01/12-5-million-homes-put-in-foreclosure-2007-2012/; Lam Vo, “ll The Wealth We Lost And Regained Since The Recession Started,” NPR, available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/money/2013/05/31/187548260/all-the-wealth-we-lost-and-regained-since-recession-started

[27] “The Recession of 2007-2009,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Feb. 2012, available at: http://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2012/recession/pdf/recession_bls_spotlight.pdf; for the real unemployment rate see: http://portalseven.com/employment/unemployment_rate_u6.jsp

[28] Matt Taibbi, “Obama’s Big Sellout,” Common Dreams, Dec. 13, 2009, available at: http://www.commondreams.org/news/2009/12/13/obamas-big-sellout-president-has-packed-his-economic-team-wall-street-insiders

[29] David Dayen, “The Most Important WikiLeaks Revelation Isn’t About Hillary Clinton,” The New Republic, Oct. 14, 2016, available at: https://newrepublic.com/article/137798/important-wikileaks-revelation-isnt-hillary-clinton

[30] Eamon Javers, “Inside Obama’s bank CEOs meeting” Politico, April 3, 2009, available at: http://www.politico.com/story/2009/04/inside-obamas-bank-ceos-meeting-020871

[31] Simon Johnson and James Kwak, Thirteen Bankers, excerpt available at: https://13bankers.com/excerpt/

[32] Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Bill Vlasic, “President Gives a Short Lifeline to Carmakers,” The New York Times, March 30, 2009, available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/31/business/31auto.html and Robert J. Samuelson, “Celebrating the auto bailout’s success,” The Washingon Post, April 1, 2015, available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/celebrating-the-auto-bailouts-success/2015/04/01/67f3f208-d881-11e4-8103-fa84725dbf9d_story.html?utm_term=.cd636a94a2e2

[33] Kevin Baker, “Barack Hoover Obama,” Harper’s Magazine, July 2009, available at: http://harpers.org/archive/2009/07/barack-hoover-obama/1/

[34] Chris Isidore, “Stimulus price tag: $2.8 trillion,” CNN Money, Dec. 20, 2010, available at: http://money.cnn.com/2010/12/20/news/economy/total_stimulus_cost/

[35] Paul Krugman, “Franklin Delano Obama?”, The New York Times, Nov. 10, 2008, available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/10/opinion/10krugman.html

[36] Andrew Fieldhouse, “5 Years After the Great Recession, Our Economy Still Far from Recovered,” Huffington Post, Aug. 26, 2015, available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/andrew-fieldhouse/five-years-after-the-grea_b_5530597.html

[37] Eric Morath, “Six Years Later, 93% of U.S. Counties Haven’t Recovered From Recession, Study Finds,” Wall Street Journal, Jan. 12, 2016, available at: http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/01/12/six-years-later-93-of-u-s-counties-havent-recovered-from-recession-study-finds/

[38] Dianne Ravitch, “The Dismal Failure of Arne Duncan’s ‘Race to the Top’ Program,” Alternet, Oct. 28, 2015, available at: http://www.alternet.org/education/dismal-failure-arne-duncans-race-top-program

[39] John Easley, “Obama Drops The Hammer On Republicans By Reminding Them Obamacare Was Their Idea,” PoliticusUSA, March 25, 2015, available at: http://www.politicususa.com/2015/03/25/obama-drops-truth-bomb-gop-the-affordable-care-act-plan-adopted-it.html

[40] Kevin Young, and Michael Schwartz, “Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: How Corporate Power Shaped the Affordable Care Act,” New Labor Forum, October 2014, at: https://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2014/10/01/healthy-wealthy-and-wise-how-corporate-power-shaped-the-affordable-care-act/

[41] “Is the Affordable Care Act Working?”, The New York Times, Oc. 27, 2014, available at http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/27/us/is-the-affordable-care-act-working.html#/

[42] Robert Lezner, “ObamaCare Enriches Only The Health Insurance Giants and Their Shareholders,” Forbes, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertlenzner/2013/10/01/obamacare-enriches-only-the-health-insurance-giants-and-their-shareholders/#7572e8530776

[43] Obama speech video from BuzzFeed available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yUWJHmRjJy0 and Josh Hicks, “Obama’s failed promise of a first-year immigration overhaul,” Washington Post, Sept. 25, 2012, available at:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/post/obamas-failed-promise-of-a-first-year-immigration-overhaul/2012/09/25/06997958-0721-11e2-a10c-fa5a255a9258_blog.html?utm_term=.cad4b51d4ba4

[44] Ezra Klein, “READ: President Obama’s immigration proposal,” Washington Post, January 29, 2013, available at:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/01/29/read-president-obamas-immigration-proposal/?utm_term=.dd4207973a45

[45] Serena Marshall, “Obama Has Deported More People Than Any Other President,” ABC News, Aug. 29, 2016, available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/obamas-deportation-policy-numbers/story?id=41715661

[46] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/west-virginia-right-to-work_us_56be2341e4b0c3c5505124f6

[47] Forum: Assessing Obama’s Record on the Environment,” YaleEnvironment360, no date, available at: http://e360.yale.edu/features/forum_assessing_obamas_record_on_the_environment

[48] Ibid.

[49] Dyson, The Black Presidency, pp. 17-32.

[50] NAACP President Ben Jealous, “Blacks Doing Worse,” YouTube, Jan. 27, 2013, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phAlz2XKJPo

[51] Brennan Williams, “Tavis Smiley: ‘Black Americans Have Lost Ground Under Obama’,” Huffington Post, September 12, 2014, available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/12/tavis-smiley-black-americans-obama_n_5812020.html

[52] Thomas Frank, “Cornel West: “He posed as a progressive and turned out to be counterfeit. We ended up with a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency,” Salon, Aug. 24, 2014, available at:

http://www.salon.com/2014/08/24/cornel_west_he_posed_as_a_progressive_and_turned_out_to_be_counterfeit_we_ended_up_with_a_wall_street_presidency_a_drone_presidency/

[53] Rakesh Kochhar and Richard Fry, “Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession,” PewResearchCenter, Dec. 12, 2014, available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/12/racial-wealth-gaps-great-recession/

[54] William A. Darity, Jr., “How Barack Obama Failed Black Americans,” The Atlantic, Dec. 22, 2016, available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/12/how-barack-obama-failed-black-americans/511358/

[55] Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Chicago: Haymarket, 2016), p. 170.

[56] Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, pp. 160 and 169.

[57] Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, p. 78.

[58] Dyson, Black Presidency, pp. 24 and 25.

[59] See Iraq Body Count at: https://www.iraqbodycount.org/

[60] Daniel Trotta, “Iraq war costs U.S. more than $2 trillion: study,” Reuters, March 14, 2013, available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-war-anniversary-idUSBRE92D0PG20130314

[61] Mark Thompson, “The True Cost of the Afghanistan War May Surprise You,” Time, Jan. 1, 2015, available at: http://time.com/3651697/afghanistan-war-cost/

[62] Edward Delman, “Obama Promised to End America’s Wars—Has He?”, The Atlantic, March 30, 2016, available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/03/obama-doctrine-wars-numbers/474531/

[63] “Sustaining U.S. Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense,” available at: http://archive.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf

[64] Scott Shane, “Drone Strikes Uncomfortable Truth: US Is Often Unsure about Who Will Die,” The New York Times, May 24, 2015, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/24/world/asia/drone-strikes-reveal-uncomfortable-truth-us-is-often-unsure-about-who-will-die.html?_r=0

[65] “Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Expanded Corporate Power, Lower Wages, Unsafe Food Imports,” Public Citizen, no date, available at: http://www.citizen.org/TPP

[66] George Monbiot, “This transatlantic trade deal is a full-frontal assault on democracy,” The Guardian, Nov. 4, 2013, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/04/us-trade-deal-full-frontal-assault-on-democracy

[67] Dyson, Black Presidency, p. 3.

[68] Robert Reich, “Who Lost the White Working Class,” available at: http://robertreich.org/post/137631700920

[69]“A Deep Dive Into Party Affiliation: Sharp Differences by Race, Gender, Generation, Education, Pew Research Center, available at: http://www.people-press.org/2015/04/07/a-deep-dive-into-party-affiliation/

“The Russian invasion of Ukraine has no justification, but NATO…” It is difficult to describe the emotions I and other Ukrainian socialists feel about this “but” in the statements and articles of many Western leftists. Unfortunately, it is often followed by attempts to present the Russian invasion as a defensive reaction to the “aggressive expansion of NATO” and thus to shift much of the responsibility for the invasion to the West.

“The Russian invasion of Ukraine has no justification, but NATO…” It is difficult to describe the emotions I and other Ukrainian socialists feel about this “but” in the statements and articles of many Western leftists. Unfortunately, it is often followed by attempts to present the Russian invasion as a defensive reaction to the “aggressive expansion of NATO” and thus to shift much of the responsibility for the invasion to the West.

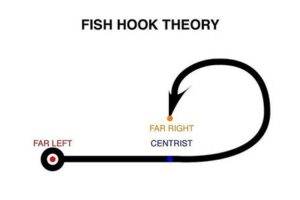

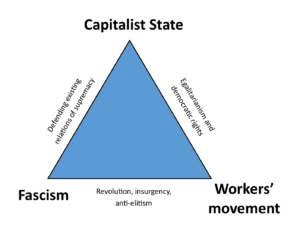

The Fishhook Theory is the equal-but-opposite counterpart to the Horseshoe, which argues that in fact it is the political centre (aka “the Establishment”, or even “the Libs”) who are close to or even identical with fascists. This harks back to the infamous “Third Period” analysis of German Communists in the 1930s, who described the centre-left Social Democrats as “social fascists”, and accordingly downplayed the threat of the actual fascists taking power; much like the edgy online Left today mock those worried by the threat of “Trump 2.0” or military victories for Putin.

The Fishhook Theory is the equal-but-opposite counterpart to the Horseshoe, which argues that in fact it is the political centre (aka “the Establishment”, or even “the Libs”) who are close to or even identical with fascists. This harks back to the infamous “Third Period” analysis of German Communists in the 1930s, who described the centre-left Social Democrats as “social fascists”, and accordingly downplayed the threat of the actual fascists taking power; much like the edgy online Left today mock those worried by the threat of “Trump 2.0” or military victories for Putin.

[Presented at American Sociological Association meeting, Montreal, August 2024 and partially drawn from introduction to my new book, A Political Sociology of Twenty-First Century Revolutions and Resistances (Routledge 2024)]

[Presented at American Sociological Association meeting, Montreal, August 2024 and partially drawn from introduction to my new book, A Political Sociology of Twenty-First Century Revolutions and Resistances (Routledge 2024)]

Fascism is terrifying. The sight of hundreds of racists tearing through your community and intimidating racialised minorities strikes you with an almost paralysing fear. It disempowers you, recasts where you live in a darker light and breeds a disabling paranoia about the people you share the world with. I fucking hate fascism.

Fascism is terrifying. The sight of hundreds of racists tearing through your community and intimidating racialised minorities strikes you with an almost paralysing fear. It disempowers you, recasts where you live in a darker light and breeds a disabling paranoia about the people you share the world with. I fucking hate fascism.

This is the ninth of a series of articles about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, but the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candidates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

This is the ninth of a series of articles about Black political candidates for the two highest offices of president and vice-president of the United States. The idea of writing this series originally begun when Cornel West announced his candidacy, but the story of Black political candidates for the highest offices take on a new significance in light of Kamala Harris’ current campaign. This is the list of candidates that we discuss in this series, though the four candidates of 1968 are discussed in one article.

Any protest against war in the Middle East that only focuses on the role of Israel and the U.S./U.S. allies, and does not oppose the role of the Iranian government, is a capitulation to Iranian imperialism and a betrayal of the ongoing popular struggles inside Iran.

Any protest against war in the Middle East that only focuses on the role of Israel and the U.S./U.S. allies, and does not oppose the role of the Iranian government, is a capitulation to Iranian imperialism and a betrayal of the ongoing popular struggles inside Iran. The Left has focused on support for vouchers in Harris’ running mate but has missed that in either a Harris or Trump presidency, we’ll need to fight powerful elites to save public education

The Left has focused on support for vouchers in Harris’ running mate but has missed that in either a Harris or Trump presidency, we’ll need to fight powerful elites to save public education

When International Brotherhood of Teamsters President Sean O’Brien announced he was going to speak at the Republican National Convention I was more ambivalent than many of those on the Left. Yes, Trump is abominable but the labor leaders speaking out for the Democrats are tying themselves to accessories to mass murder. They’re not exactly bringing honor to the House of Labor either. Presumably some of the 186,000+ dead in Gaza were union members. So it goes, “solidarity forever” again becomes “solidarity sometimes.”

When International Brotherhood of Teamsters President Sean O’Brien announced he was going to speak at the Republican National Convention I was more ambivalent than many of those on the Left. Yes, Trump is abominable but the labor leaders speaking out for the Democrats are tying themselves to accessories to mass murder. They’re not exactly bringing honor to the House of Labor either. Presumably some of the 186,000+ dead in Gaza were union members. So it goes, “solidarity forever” again becomes “solidarity sometimes.”

It was her father who launched her political career when in 1986 he urged a write-in campaign for her as a candidate for the Georgia House; she lost, but garnered 40 percent of the vote. She ran for the same seat again in 1988 and won, serving alongside her father.

It was her father who launched her political career when in 1986 he urged a write-in campaign for her as a candidate for the Georgia House; she lost, but garnered 40 percent of the vote. She ran for the same seat again in 1988 and won, serving alongside her father.

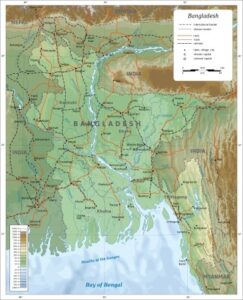

Right now, Bangladesh has been functionally turned into a prison and a graveyard. Students have observed a nationwide strike across Bangladesh on Thursday (18th July 2024) which have been called “Bangla blockade”.

Right now, Bangladesh has been functionally turned into a prison and a graveyard. Students have observed a nationwide strike across Bangladesh on Thursday (18th July 2024) which have been called “Bangla blockade”.

In the short term, we are often caught between our dreams and realism. But there is a chance right now to offer a suggestion for the Democratic Party’s vice-presidential pick that would be both inspiring and eminently practical, namely, Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers.

In the short term, we are often caught between our dreams and realism. But there is a chance right now to offer a suggestion for the Democratic Party’s vice-presidential pick that would be both inspiring and eminently practical, namely, Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers.